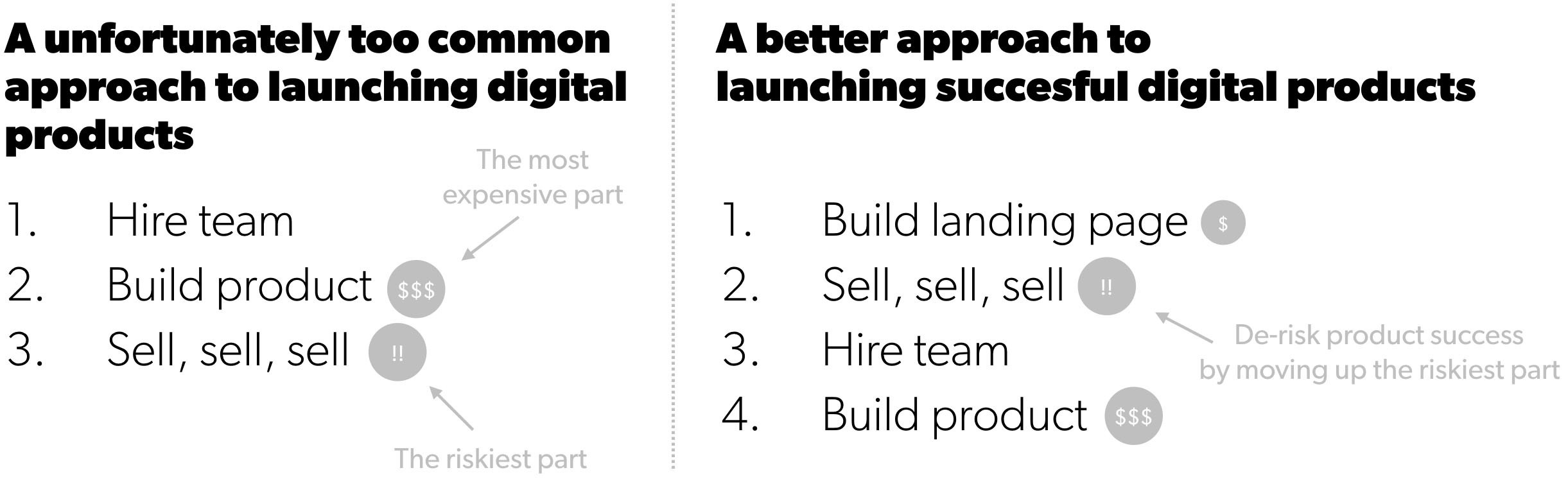

The starting point when launching a new product is too often to ask yourself: What product do we need and what team should we hire? Then after building the product, you start figuring out how to sell it or if it can be sold in the first place, which is actually the most riskiest part.

Too many companies are focused on making their idea happen with the result of building something nobody wants. They start with the most expensive part; hiring a team and building an actual finished product, and address the most riskiest and critical assumption at last; whether anybody is interested in the built product. Instead, turn that upside down: address your most riskiest assumption as your first action by producing hard evidence that users have the problem you are addressing and are willing to pay money for your intended solution.

A much better approach is to start testing whether you can sell the product in the first place, before you start building it. Or even better, start by examining whether users have the problem you are trying to solve for them in the first place.

Instead of testing an actual product, start by testing what unique selling points of your future product customers would respond to better. Explain why users should buy your product and research what arguments you need to use to persuade them. Before writing a single line of code.

Some would argue that you can’t sell a product you haven’t built yet. I would argue that it is better to start testing whether people would buy, or at least have them acknowledge and sign up for buying when your product is done.

What’s wrong in the first approach is that the most expensive part (building the product) comes before the biggest risk (whether you can sell your product or not). A much better approach is switching it around so that you get the most riskiest part out of the way before you start committing to anything expensive.

The perfect tool for de-risk your product development is experimentation. One such experiment could be putting together a landing page – a feat easily accomplished with one of the many no-code landing-page builders such as Carrd, Instapage, Unbounce or Leadpages.

So how would such an experiment look like?

Buffer: From idea to paying customers in 7 weeks

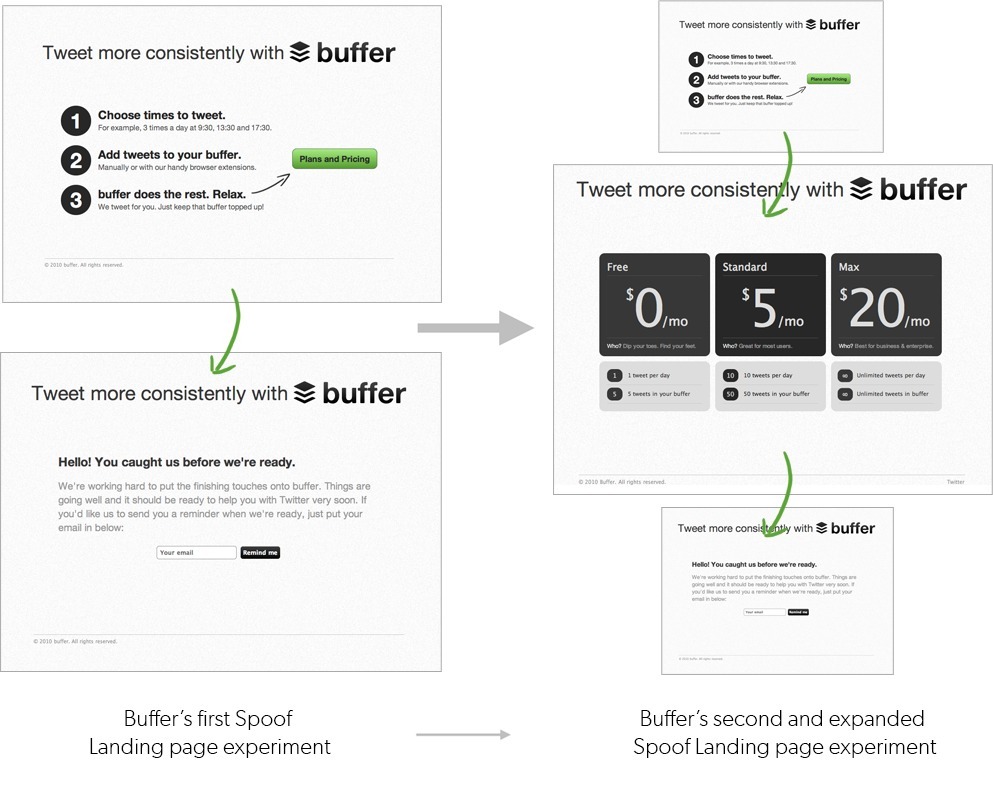

When the social media sharing service, Buffer, first launched, there was no working product. The product was a two-page landing page test designed to test whether potential customers would even consider using the app.

On the first of the two pages, a button labeled “Plans and Pricing” encouraged users that were interested in learning more. Clicking on the button would take users to a second page, explaining that there wasn’t actually a product – that it was just a cleverly designed test. Looking at the conversion rate from page one two page two as well as interacting with however left their email address and commented on twitter, this initial product was deemed validated.

If the result would have been different, another landing page could have been drawn up – and another one after that until the product had reached the desired outcome.

Having considered the first test validated, Joel Gascoigne of Buffer, moved on to test willingness to pay by adding a pricing page in between the original two pages. The second test constructed a higher hurdle adding one extra click until users would give up their email providing more solid evidence of how keen users were. But more importantly, it simulated a “pay now” experience, constructing a Dry Wallet experiment.

Had the experiment not produced satisfying results, Joel could have tried with more variations and continued to perfect his communication and flow until he had proof that the solution he had thought up matched how customers managed to formulate their problem.

You don't have to involve engineers

To test whether his product idea had any merit, Joel Gascoigne did an experiment. Even though Joel had the ability to code software himself, the experiment didn’t involve any engineering work or any lines of code written. He didn’t even involve a designer.

Had Buffer instead went out to build actual stuff, getting feedback and market validation from real customers, the process would have been slow and expensive. Instead, Joel managed to get real hard evidence that he was on the right path, why continuing to build the actual product was a no-brainer.

Sources

1 Joel Gascoigne, 2011, Idea to Paying Customers in 7 Weeks: How We Did It, Buffer Blog

2 Anders Toxboe, 2019, Spoof Landing Page Experiment, learningloop.io

3 Anders Toxboe, 2019, High Hurdle experiment, learningloop.io

4 Anders Toxboe, 2019, Dry Wallet experiment, learningloop.io