It is a proven fact that 80 percent of the effects in a system are generated by 20 percent of the its variables. Use this to prioritize your design efforts.

The 80-20 rule claims that for any large system 80 percent of the effects are generated by 20 percent of the variables in that system. The rule has proven true in all large systems including those in user interface design as well as economics, management, quality control, and engineering among others.

The exactness of the percentages in the 80-20 rule is for illustration purposes only, why the rule has also been called Paretos Principle, Juran’s Principle, Vital Few, and the Trivial Many rule. There are plenty of examples of 90-10, 70-30, and 95-5 rules to underline the non-exactness of the 80-20 rule while also emphasizing its universal utility.

Examples1 of the 80-20 rule include:

- 80 percent of a product’s usage involves 20 percent of its features.

- 80 percent of a town’s traffic is on 20 percent of its roads

- 80 percent of a company’s revenue comes from 20 percent of its products

- 80 percent of innovation comes from 20 percent of the people

- 80 percent of progress comes from 20 percent of the effort

- 80 percent of errors are caused by 20 percent of the components

Use the 80-20 rule to focus your resources in order to realize greater results. Identify what 20 percent of a products features are used 80 percent of the time and concentrate design and testing efforts on those resources. Or identify what critical 20 percent of a product’s features are responsible for 80 percent of the revenue and concentrate on that.

The 80-20 rule can help you decide what to redesign, what parts of a product or your time to downplay, what to throw away, or where to invest your scarce resources. It can help you resist efforts to correct and optimize designs beyond the critical 20 percent as more would yield diminishing returns.

The principle was originally used by the Italian sociologist and economist Vilfredo Pareto in 1906 to describe the unequal distribution of the Italian wealth where 20 percent of the people owned 80 percent of the wealth.

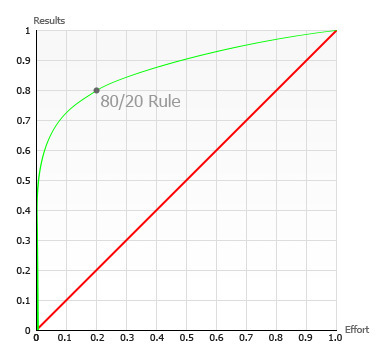

The 80-20 rule displayed as a graph (green line). If all effort yielded equal results, the red line would be valid.

Discussion

The essence of 80-20 rule is that things are not distributed equally. Each unit of work does not contribute to the same amount. In the perfect world, every employee would contribute the same, every bug be equally important, every feature equally loved, and planning would be simple.

The ratio can change and does not need to be 80-20. It could even be 90-20 (the numbers does not need to add up to 100). 20 percent of a workforce could be responsible for 90% of the results.

In economic terms there is a diminishing marginal benefit of adding extra resources. It can be argued that this also relates to the law of diminishing returns as at specific point, adding an extra worker will yield less marginal benefit than the worker added before. Using resources on the last minor details will not produce as much value as the resources used to build the core fundamentals of the product4.

A technique for prioritizing what tasks to focus your resources on is to categorize your tasks as A, B, and C – where the tasks marked with an A will yield greater results than tasks marked with a B, which will yield greater results than the tasks marked with a C. In many cases, the different tasks would not be prioritized in order of what will yield the most value, but rather what we think is the coolest. A sequence of tasks could be A,C,B,A,C,C,B,A,C,A – where if we were able to prioritize these tasks in the order of A,A,A,A,B,B,C,C,C,C it can be argued that we would end up with an end-product of much higher value with a given amount of resources available.

Source

1 Universal Principles of Design, William Lidwell et. al., p. 12, Rockport Publishers, 2003

2 Vilfredo Pareto_, Wikipedia.comPareto, August 21st, 2008

3 Pareto principle_, Wikipedia.comrule, August 21st, 2008

4 Pareto Principle, Better explained, August 21st, 2008

Read my earlier blog post on Prioritization of features explained graphically for more explanation and examples of this design principle.

7 comments

Anton on Jun 18, 2009

This is a good reminder to concentrate on the vital parts of the product, and also to simplify the product to those key parts.

Also, a cool point about 90-20 – the percentages are indeed from different metrics, so don’t have to add up :)

I would highlight, though, that the idea of diminishing returns works only if the tasks are prioritized by the importance, and if people are ordered by their input. Otherwise the tenth person you add to the team may be the one who will produce the 90% of the resulting output.

pay per click Dubai on Aug 25, 2009

Well explained 80-20 rule. And i agree with what above poster said about the idea of diminishing returns.

Custom Website Redesign on Aug 27, 2009

That is just so true. The Pareto principle works in every stream of life and even in stock trading. Only 20% of your stocks will give you 80% of your benefit. Not sure if this holds true for Mr. Warren Buffet though.

PDF guide on Oct 23, 2009

Interesting blog..have bookmarked this page so keep up the good work!

maternity leave on Oct 23, 2009

Interesting blog..have bookmarked this page so keep up the good work!

motorola software on Nov 04, 2009

Have really enjoyed reading this. Keep up the good work, have bookmarked this page.

how to sell ebooks on Feb 09, 2010

Everyone can write, but not everyone can share information in an attractive way. Good work!

Comments have been closed