72% of all new products flop1. In other words: it is most likely that you are working on something nobody wants. Chances are higher that you will succeed with an alternative version of the idea you are working on right now – or something completely different altogether.

However good your idea is, you have to admit that you have no proof. That is the hard part. If you don’t admit that uncertainty is at its maximum when you are first starting out, you’re going to go off and implement something nobody wants.

Too many startups and enterprises neglect to admit uncertainty and assume that they are going to be successful. When we assume that we are going to be successful, we tend to skip the obvious experiments.

72% of all new products flop

The path from idea to successful product isn’t straight

Too many start-ups and enterprises assume that their product idea will work and jump straight to building their product. They skip the obvious experiments. They assume that customers will want it, know how to use it, and know where to find it. They assume that they can make sufficient money from their product idea and produce it at a low enough cost to create a viable business. They assume that they know how to build it and bring it to life.

Having admitted that you have no proof that your idea will work, the next logical step is to start producing the evidence. The most expensive way to produce evidence that your idea will work is to go out and implement it. Building actual stuff. A much cheaper way is through rapid product experimentation.

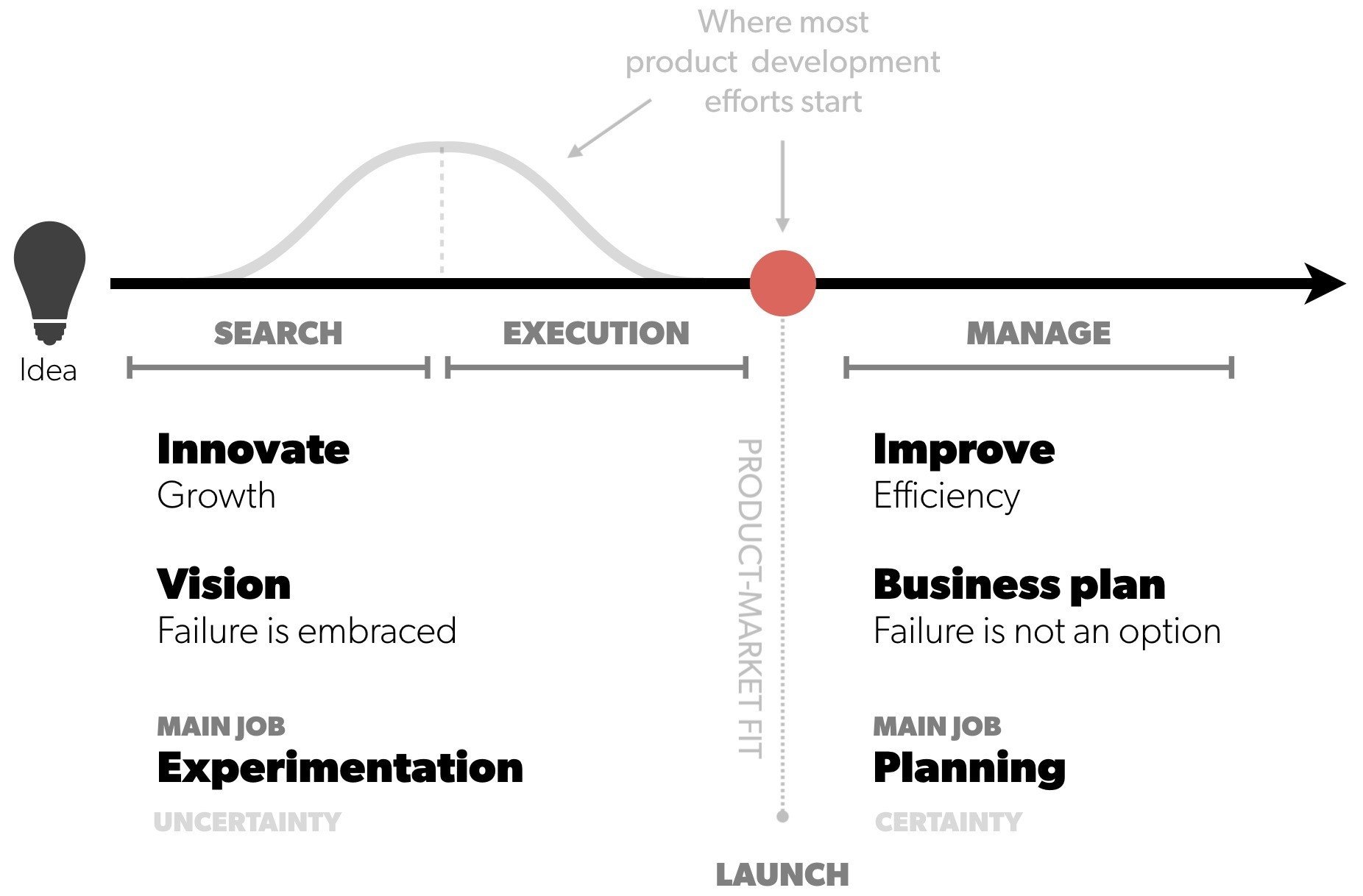

Acknowledging that there is important work to be done searching for the right way to implement your idea, before your start executing, is the first step to ensure the success of your future product or feature.

This kind of work is called product discovery for which the main job is experimentation.

The wrong place to start: creating a business plan

Too many companies try to innovate as if they were already successful. As startups and enterprises embark on bringing a product idea to life, a typical first task is creating a business plan full with spreadsheets forecasting cost and revenue. This will lead them astray.

The problem with business plans is that the expectation is to implement them.

The problem with business plans is that the expectation is to implement them. The problem with having a business plan is that it maximizes the risk of failure, if we are first starting out. At this point business plans are a waste of time.

When you haven’t validated your idea yet, business plans are a waste of time. There is no way you can get a business plan right the first time.

The danger of business plans in the very beginning is that we tend to put numbers in them that are at best educated guesses. Even though it may seem harmless at first to make an educated guess at a conversion rate or the willingness to pay, the problem comes after we have entered the numbers.

At that point we tend to forget that the numbers we put in the plan were only guesses. Instead we start treating the numbers like they were real. But they are not. They are only fantasy. As we add more fictional numbers and variables to our business plan it only gets worse as we then only add to the uncertainty of the plan – and the risk of failure of that business plan.

The business plan tool is great for execution. That as a problem as the intention is to implement them.

When our numbers are only guesses, business plans don’t tell us anything real. Instead they focus execution on something that has no proof. In the very beginning, using business plans is dangerous as they only help aid our overall confusion, at a time when we expect them to guide us down the right path of execution.

A better place to start: experimentation

It doesn’t make sense to implement a product idea, if we have no evidence that points to its probable success.

Instead, when we are first starting out, we should rather focus on establishing a baseline. We should focus on discovering the kind of conversion rate can we expect from specific customer segments. On what kind of money can we charge for our product and on what basis. But before that: focusing on discovering the needs, pain-points, and wants of our customers. What problems do they struggle with and how can we help them best resolving them?

It doesn’t make sense to implement a product idea, if we have no evidence that points to its probable success.

Embracing an innovation mindset

In the very beginning, before we have a proven business case, our mindset should be different from the execution mindset of a business plan. When we are first starting out and uncertainty is at its maximum we want to do innovation work rather than improvement work. Our focus should be on maximizing discovery and growth rather than delivery and efficiency.

Too many starts up and enterprises start out assuming product success - as if they already have an succesful product. This leads to adopting the faulty mindset of efficiency rather than that of innovation. They end up focusing on planning rather than experimentation with the result of implementing something nobody wants.

Instead of using business plans to guide our actions, our north star should be a vision. Where a business plan is focused on implementation of an agreed upon solution, a vision allows for exploring multiple opportunities, throwing those away along the way that doesn’t work. Using a vision as a guiding light rather than an implementation-plan will help embrace any failure we will undoubtedly run into along the way toward creating a successful product.

Committing to a business plan will lock you in

Funding for an idea is typically secured with leadership or investors by selling them a business plan. When the underlying business-, customer-, and technical assumptions of a polished and refined business plan is yet to undergo rigorous testing, that is a problem

When leadership and investors buy and finance a business plan, they expect that success is an execution problem and that projections will materialize exactly as described. In this case, changing direction later on will be difficult, as you sold leadership or investors something else.

Lock in on opportunities rather than solutions

Instead of selling leadership a refined and detailed execution plan, sell an opportunity and a rigorous and rapid experimentation process that will turn your product idea into an executable business plan by producing evidence from real customers in the (right) market.

Explain how this will allow leadership and investors to de-risk their investment by minimizing the risk of failure. That committing to a business plan when you are first starting out will maximize the risk of failure by locking in to one direction, that still remains to be proven.

An even bigger risk than building something that nobody wants is scaling it prematurely. This can happen if you get into execution mode too early before finishing searching for a solution that is both desirable, viable, and feasible.

A business plan represent one specific solution to a problem. Don’t invest in execution of a specific solution until you have strong evidence that it will work.

Sources

1 Simon-Kucher & Partners, 2014, Global Pricing Study 2014

2 Toxboe, 2019, Don’t trust agile alone to build successful products