One of my life goals is to publish a book about how to build great products. I hope to help others learn from my hard-earned lessons to get ahead of the game. Ultimately, I want to help product builders to kick ass at what they love to do.

It’s a dream I’ve had for more than a decade. Not only because I would love to see my name on the cover of a great book, but also because I believe I have a story to tell.

Throughout my professional life, I’ve held most of the roles involved in building great digital products. I’ve been a developer, a software architect, a designer, a user researcher, content producer, a product owner, an agile coach, a business developer, marketing manager, division manager, board member, business coach, and founder. I’ve seen and experienced it from most angles.

While I’ve had my share of failures, I can also see that how we’re approaching things now, is so much more effective than when I first started out.

I believe I have a story to tell and something valuable to teach.

So why don’t I just write the book? Well, I want it to be a success as well. I want to be confident that what I have to teach is relevant – that it will actually help people get ahead of their game. I don’t want to waste my time, if nobody will end up buying or reading it.

A bunch of unknowns has stopped me from creating the instant blockbuster that I’ve been dreaming of. For that to happen, I need to narrow down the topic, the content, the case studies I put in the book, the tone of voice, the narrative, the marketing, my target audience, and probably a few more variables. There is a great deal of research that needs to be made in order for my book project to even start making sense.

Testing the topic

I decided that the first and most critical unknown to test was the topic: was what I had to tell even interesting to begin with?

In October 2017, it was my turn to give a presentation at my local networking group of solo marketing professionals. I needed a catchy title, and called the presentation “Validate or Die”. My fellow peers were being nice to me. Thanks to them, I didn’t lose all motivation after my horrendous first attempt.

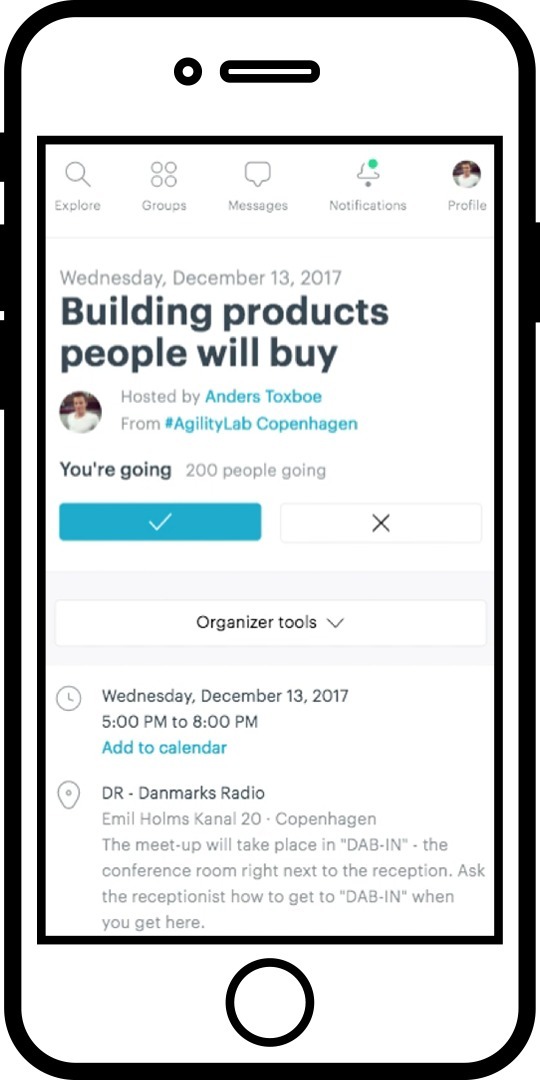

The Meetup landing page for my first public test event experiment in December 2017. 200 people showed up.

On the contrary, I got a taste of what could become. I had a good hunch of being on to something that I just couldn’t articulate perfectly yet. I got great validation that the topic was interesting and even better feedback as to how to improve.

December 13th, 2017 was the date for my next test: I was speaking at a local monthly Meetup on Agile development. For this test, I wanted to find out whether my chosen topic was interesting for complete strangers and not only my friends. Could I get people, who weren’t involuntarily committed to showing up and hearing me out, to come see me. Would they find my story interesting? Could I get them to spend their afternoon in my company, with the promise of teaching them a valuable lesson?

I decided on a title I saw fitting for the story I had to tell: “Building products people will buy”. The title certainly proved successful in getting people to show up: 200 came – 3 times the norm for the Meetup group. I did, however, learn that it made sense to tone it down for future tests to match audience expectations.

Still, I had struck a nerve. It wasn’t just me who was struggling with building successful products. On the contrary, it was a topic that had more attraction than any other I had talked about previously.

Putting on an event worked great in terms of uncovering market demand (would people show up) and in the process, I had the chance to learn how people reacted to what I had to say. Suddenly, I had a medium to test my case studies and I could play around with several ways of delivering on the same point. I could gauge when the audience was growing tired and when I got them excited. In that process, I discovered what I had to do to keep them engaged.

I also learned what kind of people I could attract with the topic and talk. It was primarily UX professionals, agile professionals, and product managers.

Testing willingness to pay

One thing is to show up for an event to hear me speak or read one of my blog posts. While that did tell me something about whether my value proposition was worthwhile, having people show up for an event didn’t provide evidence that they would also be interested in paying up money for a potential book on the topic.

Optimally, I wanted to test willingness to pay for a future book. However, with a full time job at the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (the Danish BBC), managing the digital development branch with a staff of almost a hundred, I needed to settle on something smaller and more manageable.

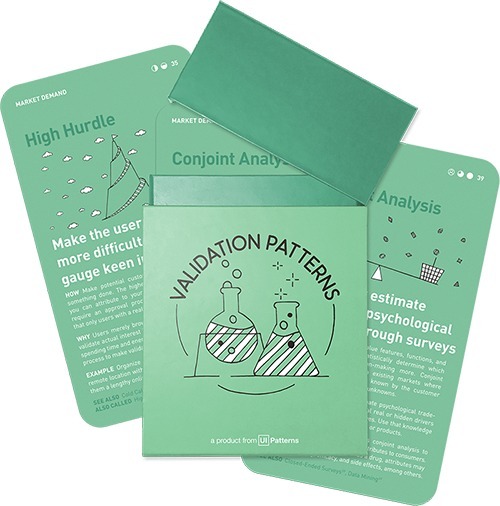

The Validation Patterns card deck, a slimmed down version of the book I wanted to write, started its life on a pre-order landing page.

To test my target audience’s willingness to pay for my future book, I settled on a smaller version that would cater to the same market with the same value proposition. Instead of spending months researching the topic, I finished the first 6 card decks (out of 100 in total brainstormed) so that I could get a sense of the deck and had material for a landing page with an option to pre-order the future card deck. If enough would buy the card deck, I would finish the research, produce, and ship it.

This seemed like the optimal way to test willingness to pay for the problem space: that “testing products is hard and time consuming. As I had previously had success creating and selling UX related physical card decks to be used for UI design and persuasive design, I felt comfortable that creating card deck would be a manageable feat within 4-5 months – even though that alone would take months of research and production.

I used marketing data from one of my other card decks to establish a baseline. I decided that if a pre-order landing page for a new card deck on lean experimentation could generate a general conversion rate above 5% or higher, that would be defined as a success as it then be on par with my other products.

The pre-order page helped me further establish a key metric that would define when I had found a sufficient fit between the story I was telling at meetups and conferences and the corresponding willingness to pay of my audience.

I also made sure to book enough free speaking engagements over the next months that I had a steady KPI to follow. Over the next few months, I managed to lift the conversion rate of audience purchases went from around 0,5% to around 10%. 2 years later, I regularly see conversion rates double that.

Get your card deck today

Playing around with the outline of the book

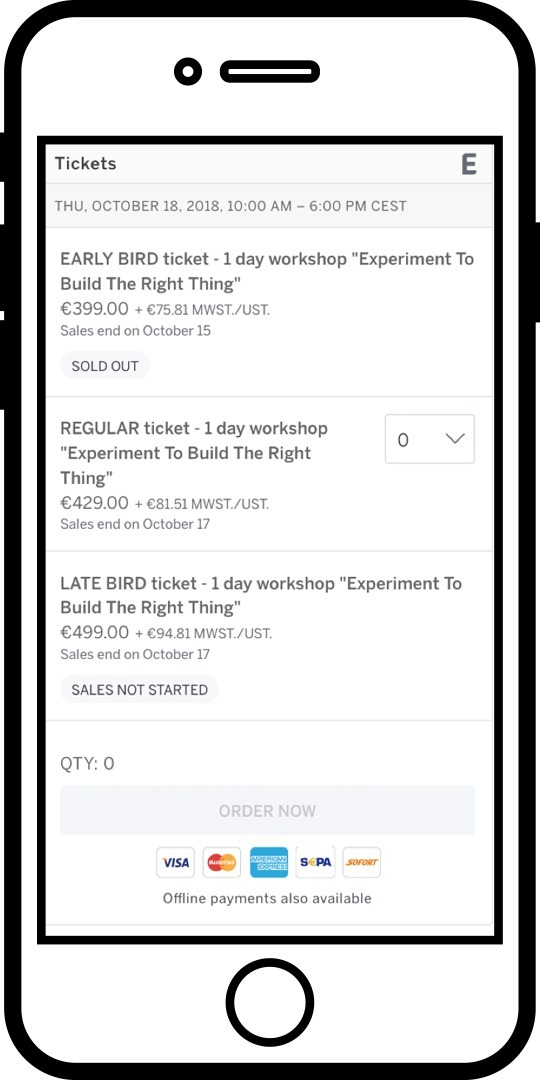

Having a paid workshop on the topic sell out, provided further proof that the problem was worth solving and proved willingness to pay at a significant higher price point ($450 vs $59).

To continuously test my progress and build momentum, I booked regular speaking opportunities, doing the same talk over and over again.

At one point, I found myself speaking at rather large conferences and accepted to host a full-day workshop on the topic of lean experimentation. However daunting it was to go from a 45-minute presentation to an 8-hour long masterclass, it provided a great opportunity.

Putting together an 8-hour workshop, I could start playing around with the outline of the potential book. I could start constructing and testing a narrative beyond what was just a 45-minute facade. I now had a medium to test learning and comprehension of my most important points as I added working exercises to the mix.

Furthermore, by selling a workshop, I would also test a new pricing point for the topic. The full-day workshop cost €399 ($450) – a significant increase from the $59 for a card deck.

As I returned from my first sold-out workshop, I was ecstatic. I quickly made sure to book new workshops that I could further learn from. In the beginning, most was free. As I grew to feel confident I had a valuable enough product to offer, I expanded the offering to be a 2-day stand-alone intensive crash-course in lean product experimentation.

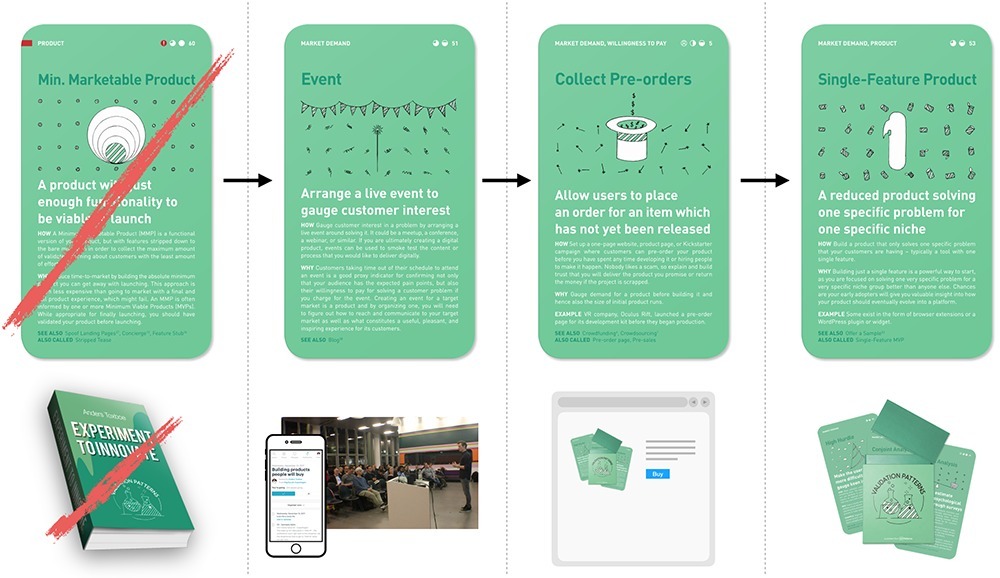

Experiment pairing: One experiment leads to the next

With the end goal of writing a book, I continuously found myself regrouping to find new ways to test and meet the demands of my audience. To begin with, the certainty of writing an instant blockbuster was too low to justify the overwhelming task of writing a full book.

Instead I chose to embark on a continuous journey of experimentation where one experiment would lead to the next as results became satisfactory.

I started out abandoning my first intended solution: publishing a book. Instead, I chose a series of experiments that would instead help me fulfil my overwall vision.

Once I received satisfactory turnout and feedback from events, I journeyed into crafting a card deck – a slimmed down version of the book. But before I went out had the card deck produced, I created a pre-order page to ensure that production wasn’t initiated until I had evidence that customers would actually buy the end-product.

Having established one experiment, I didn't need to start all over as I endeavoured into the next experiments. As I found new experiments could build on previous experiments, I also learned that certain experiments pair especially well together.

I found that I could build upon previous experiments without throwing it all away. Establishing a pre-order landing page made it straight-forward to follow up with a series of new experiments to further my learning.

After launching a landing page, I had somewhere to point my test ads and examine their effect all throughout the funnel. As I had users coming to the landing page, I could start surveying them using pop up micro surveys. Having a landing page to link to meant that the effectiveness of writing blog posts could be measured in terms of sales generated.

I added each new experiment incrementally to refine and clarify my learning along the way. One experiment leads to the next. Had I stacked all of the experiments together to address all of the risks in one shot, it would have taken forever to get out the door and I wouldn’t have had a chance to tell which experiments to stack. My learning along the way informed me about what to do next. Instead, I increased the strength of evidence along the way with small and integrated experiments so that I had reassurance that I was on the right track.

Innovation is not a straight line

While the story I just told might sound like I was on a Sunday stroll on a bed of roses, that is far from the truth. Along the way, I had cringe-worthy talks, months without any card deck orders, cancelled conference-workshops and stand-alone workshops. I even ended up refunding not only a paid ticket, but also the participant’s plane tickets and hotel rooms, as I had to cancel an unsold workshop 2 weeks before it was about to happen.

I learned valuable lessons in how the sale of a $59 card deck is a radically different process than a $1500 2-day stand-alone workshop.

Through months of experimentation, I learned how to perfect the segments and wordings of my ad campaigns, and managed to find email automation flows that proved effective.

It was a long series of trial-and-error. Luckily, I had the persistence to keep trying.

I started with the wrong perspective

I started out with a desire to see my name on the cover of a book. One of my biggest personal dreams was (and still is) to publish a book that will help others learn from my hard earned lessons so that they can get ahead of their game. Ultimately, I want to help product builders kick ass at what they love to do.

Looking back, that approach wasn’t helpful. Starting out writing the book first thing wouldn’t have led me to fulfil my vision of helping product builders kick ass at what they love to do.

Because, looking back, that was my actual vision: to help product builders kick ass at what they love to do. Instead of starting with the vision, I made the same mistake that the majority of product builders also tend to make: start with the solution.

I don’t blame them. The solution – making an idea happen or solving a specific problem is what drives us – as humans. When we lie in bed at night or when we take that shower and an idea comes to us – when we have that eureka moment, connecting all the dots necessary in making something happen: that’s what drives us and turns us on. It’s human. However, that is a problem if want to have the user in the center rather than ourselves. That is a problem if we want to make progress through experimentation.

For an experimentation mindset to be successful, we need to have our starting point in the vision rather than a proposed solution. A proposed solution, writing a book, is just one way of fulfilling the vision; helping product builders kick ass at what they love to do.

If our starting point is fulfilling a vision, then it is much easier switching to a new alternative solution as we see our first attempts fail. For that to happen, we need to change our perspective. We need to change our perspective from being excited about making a specific solution come to life, to making a vision come true.

Focusing on the vision rather than the solution sets us free. Focusing on the vision rather than the solution will allow us to pivot as we discover that users aren’t interested in our proposed solution, when we discover that we can’t build a viable solution around the intended solution, or when we discover that we can’t quite build the solution as we had first imagined.