Not all UX research methods deserve a second life.

Some are outdated. Others are misused. And a few were never that useful to begin with. Yet they continue to show up in project briefs, design sprints, and stakeholder requests—not because they work, but because they’re familiar.

As UX designers, we’re often under pressure to “do research” fast. When that happens, it’s tempting to fall back on recognizable methods that sound user-centered but don’t actually give us meaningful insights. The result? Misleading data, false confidence, and wasted time.

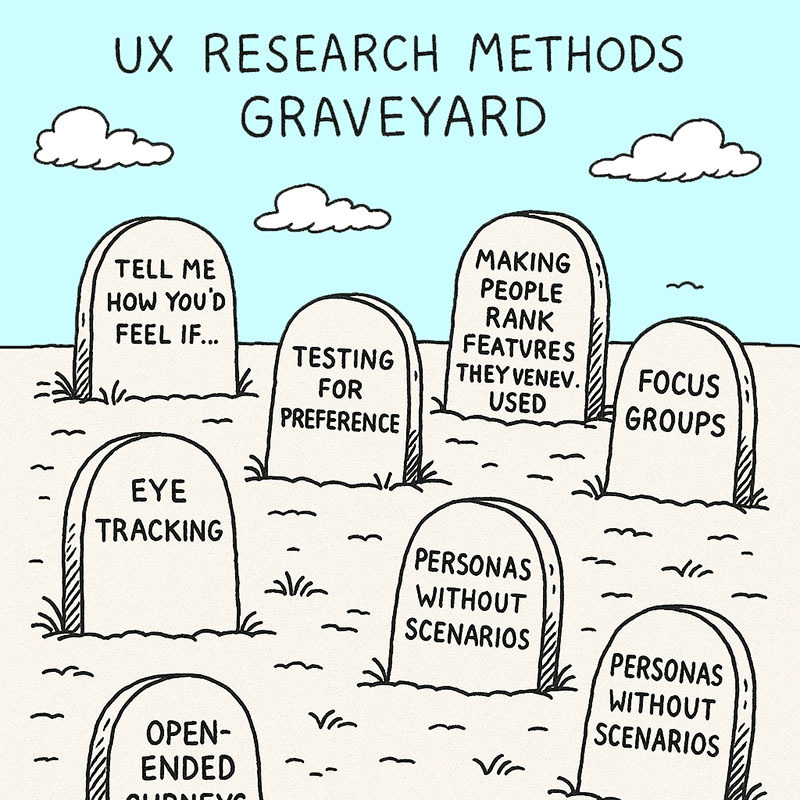

This post is a tour through the UX Research Methods Graveyard—a collection of techniques that keep resurfacing despite their flaws. Some of these aren’t inherently bad, but when misapplied (as they often are), they become more harmful than helpful.

Let’s take a closer look.

1. “Tell me how you’d feel if…”

Hypothetical questions like this aim to predict emotional reactions. But people aren’t good at forecasting feelings, especially in artificial scenarios. Answers tend to reflect what the participant thinks you want to hear, not how they’d actually feel in a real situation.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: Hypothetical emotions are unreliable data.

2. Testing for preference

“Which layout do you prefer?” may seem insightful, but preference doesn’t equal performance. A user might like how something looks but still struggle to use it effectively.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: Preferences are surface-level and often misleading.

3. Ranking features they’ve never used

It sounds logical to ask users to prioritize features, but if they’ve never used them in context, their answers are speculative at best. People tend to overvalue hypothetical benefits.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: You can’t prioritize what you don’t understand.

4. Eye tracking

Eye tracking is sometimes treated as a magic insight machine. But unless there’s a clear hypothesis and complementary data, heatmaps tell you where someone looked – not what they understood or felt.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: Expensive visuals without meaningful context.

5. “Would you recommend this to a friend?” (NPS)

The Net Promoter Score is popular in business circles, but it’s a weak signal on its own. It doesn’t explain why someone would recommend your product or what needs to change.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: It gives you a number, not a direction.

6. Focus groups

Focus groups can be useful for gathering opinions, but they’re poorly suited for understanding behavior. One dominant voice can skew the results, and social dynamics often suppress honest feedback.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: Groupthink ≠ user insight.

7. Open-ended surveys

Letting users “say anything” seems like a good idea. But unless you’re prepared to analyze the responses properly, the result is usually a pile of noise. It’s hard to compare, quantify, or act on vague, inconsistent input.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: Hard to analyze, easy to misinterpret.

8. Personas without scenarios

Personas can be useful—but only when tied to tasks and context. Without that, they become abstract profiles that don’t drive design decisions. Worse, they can turn into stereotypes.

Why it belongs in the graveyard: A name and a photo don’t guide design.

What should we do instead?

Let’s stop recycling weak methods just because they’re familiar. Let them rest in peace and make space for better practice.

These methods aren’t always wrong. The problem is in how they’re used: often too early, too casually, or without clear purpose.

Good research starts by identifying:

- What decision you’re trying to make

- What behavior you need to understand

- What data will actually help

That doesn’t require complex tools. It requires clarity and discipline. Sometimes the most valuable method is simply observing a user complete a task and asking the right follow-up questions.

If we want our research to drive better design, we need to be honest about what works, and what doesn’t.

Let’s stop recycling weak methods just because they’re familiar. Let them rest in peace and make space for better practice.