You probably have a great product. You have done your usability deeds and you have a few core customers who regularly use your product.

However, it doesn’t stick out from the competition. It has a high bounce rate, only few users return, users abandon your product faster than you would like, and in general, users never get so far as to experience all that your product has to offer.

What do you want? A one night stand or a lasting relationship?

Building persuasive user experiences is like a relationship and you need to treat it like a relationship. So, what do you want? A one night stand or a lasting relationship?

There are three common challenges of engaging users with a product:

- Sign up challenge: seducing your users. People seem interested in your software, but aren’t motivated enough to give it a try. Communicate effectively and use persuasive design principles like scarcity, completion, tunneling, the endowment effect, and social proof to move intention to action.

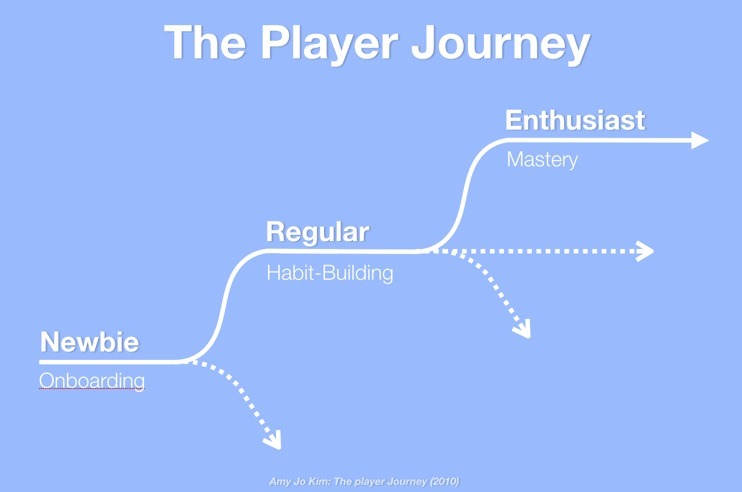

- First time use challenge: falling in love your product. People are giving your software a try, but don’t know what to do or how to get started. Better onboarding and motivational mechanisms from game mechanics can help get people started and start discovering all your product has to offer.

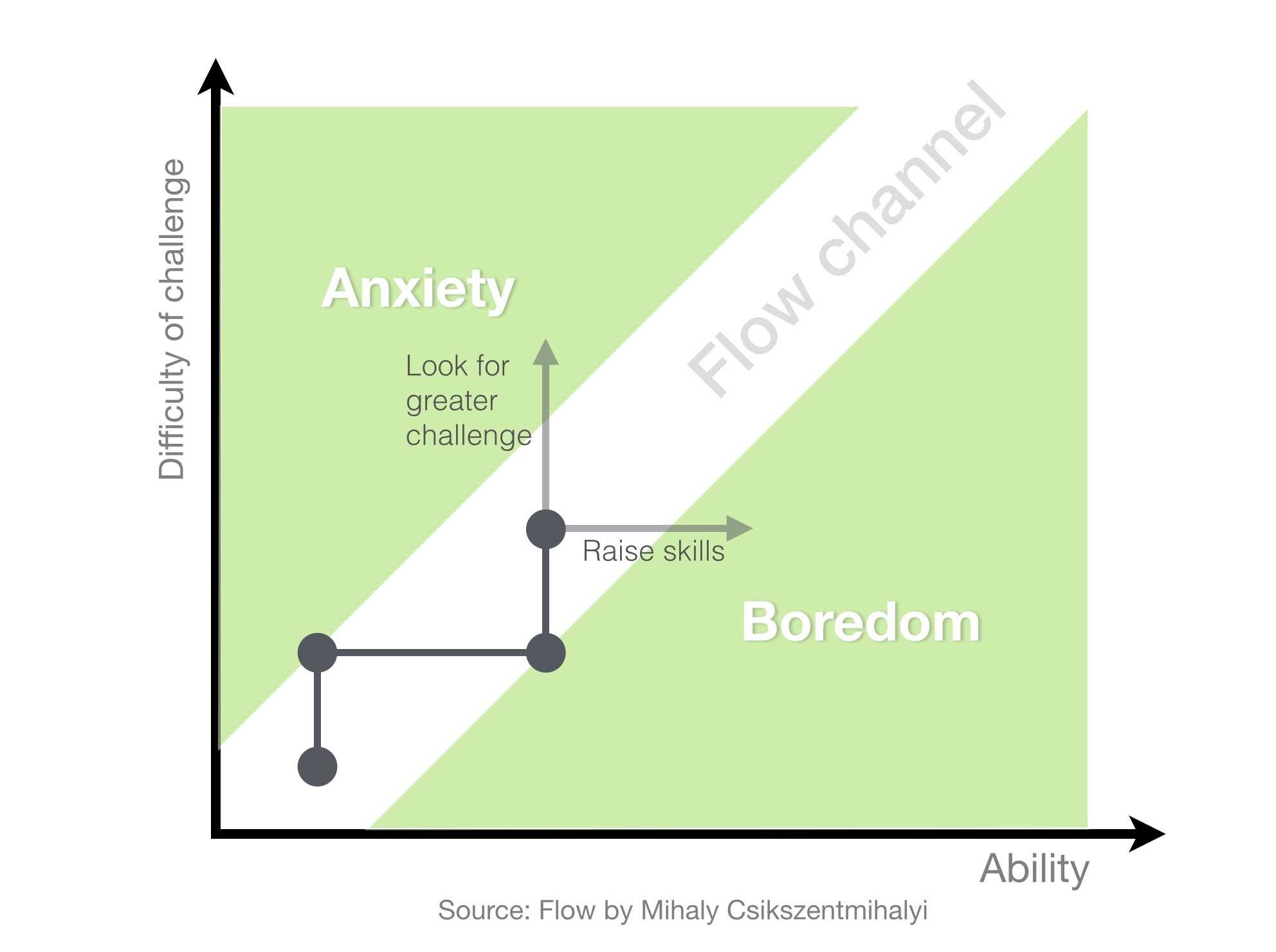

- Ongoing engagement challenge: staying in love. People get the idea of your product and use it, but they’re leaving you before you’d like. Mastery, habits, communities, sandboxes, and flow will lead to true intrinsic motivation and ongoing engagement.

Your approach to engaging users should be appropriately adjusted to the relationship you have with them. In the following, we will examine three stages a user-relationship and what tools are appropriate to use for each challenge.

Sign up challenge: Seducing your users

When we are designing our own products, we are most often too familiar with their inner workings to be good at selling them. Designers and developers tend to focus on all the features, attributes, and technical problems solved; all of which they have been preoccupied with for as far as they can remember.

When convincing users to try out your product, focusing on its features is a bad place to start.

Benefits over features

To sell your product, you should instead focus on the perceived benefits from your customers’ perspective. Instead of falling into the common trap of describing “what your product can do”, explain “what customers can do with your product”. You are not selling your product, but what you users can do with your product. People don’t buy products, they buy better versions of themselves, accomplished by using the product.. This should be your value proposition.

People don’t buy products, they buy better versions of themselves

Communicating effectively: What’s in it for the user?

The more value and relevance your message conveys, the better. Focus on what the user is going to get by using your product, rather than what they have to part with. Focus on how your product will help users be awesome rather than how much it costs or how long it will take to sign up.

Focus on what the user is going to get by using your product, rather than what they have to part with

A good way to start thinking from the perspective of your users – to step in their shoes – is to ask: What’s in it for them? Explain why it is important for potential customers to spend their precious time on your product. Explain how will it help users succeed. A good way is to actually talk to people.

Communicating efficiently: Aristotle’s 3 persuasive appeals

Aristotle’s thoughts on effective communication are over 2000 years old, but are still regarded as the basics of rhetorics to this date. His theories on public speaking are easily applied digital user experiences.

Some of his basic heuristics (rules of thumb), are his three persuasive appeals: how we must consider at least three different aspects of an argument to persuade our audience.

Aristotle’s 3 appeals were:

- Logos – appealing to logic

Appealing to logos is typically done by using fact and statistics, quotations from experts, and/or informed opinions - Pathos – appealing to emotion

Appealing to pathos is typically done by using emotional outbursts, stories about emotional events, or using picturesque and vivid language. - Ethos – appealing to ethics, moral, and character

Appealing to ethos is typically done by showing practical knowledge, showing moral character (areté), or showing good intentions and good will

When introducing your product to people, consider covering all three persuasive appeals. Are you using convincing facts, telling exciting stories about how you have helped others, and are you showing off your track record? Let’s examine how the three persuasive appeals can help you improve your user experience.

Logos – appealing to logic

You appeal to logos when you have a sound argument that in itself will demonstrate that something is the case. For example, if your blog has a lot of readers, establish social proof by displaying how many. If you have helped customers earn money, show with facts and figures how and how much.

Pathos – appealing to emotions

Given you have established trust and your argument is backed up with facts and statistics, the use of emotions can make the tipping point of a user’s decision. Appealing to emotions can help burst positive arguments or dampen negative arguments. Examples of using pathos to persuade are emotional outbursts, overstatements, narratives about emotional events, figurative or vivid language, or conveying connotative meanings. You may use pathos to appeal to humor, fear, an unjust cause, imaginations, and hopes (when you present your solution).

Ethos – appealing to ethics, moral, and character

Your audience will judge your propositions as being more true and acceptable if you establish your credibility. Establish Social Proof with the power of Authority through testimonials from credible customers, highlight how you are similar to your potential customers to induce liking and in turn their good will. Small adjustments like showing badges of affiliated industry organizations or well known customers will help boost your credibility.

Persuasion must be honest

You may think of these practices as being psychological triggers that exploit human behavior in some sort of questionable way – similar to mind control. You might also consider if these tactics are even ethical and if they are at all something you are ready to use.

Persuasion must be honest and ethically sound to continue its effect beyond just a brief encounter

If you do have these thoughts, you have the right attitude, but let’s clear up one important truth: What I explain in this article is how to tap into existing triggers based on desire, which is already part of who we are as humans. You aren’t going to convince people, that they want something, that they would otherwise not be interested in.

Persuasion must be honest and ethically sound to continue its effect beyond just a brief encounter. If you approach persuasion in a dishonest way when trying to get your users to sign up, it will eventually backfire when users eventually find out once they start using your product.

Closing the deal

So you got your users interested in what you have to offer. Your next job is to close the deal. The task is to close the deal. There are a number of techniques that will encourage users to make a decision, but we will focus on these four:

- Using the principle of Commitment and Consistency

- Utilizing the power of Scarcity

- Close off detours by Tunneling your users

- Provide samples: Give a piece of the action up front

Commitment and Consistency

People desire to act in a manner consistent with our stated beliefs and prior actions. We like to be seen as honoring our commitments consistently; as somebody who can be counted on, instead of somebody who flip flops, and is without self-control.

By getting users to state their position, declare their intentions, or show a small gesture of support, they will generally act in a manner consistent with these small requests, even if later asked to make a much larger, but consistent, commitment. Getting just a small commitment from your potential customers, like getting them to sign up for your newsletter or liking your page on Facebook, will make them more likely to purchase from you, in the future. Also, getting a small commitment is its own test, whether people are interested in the product in the first place.

If you give people all the time in the world to make a decision, they will either take up every minute of that time, or never make a decision at all.

Scarcity

If something is promoted as being scarce, it is perceived as more desirable and of more valuable to us. Simply put, people want more of those things they can have less of. The scarcity principle focuses on forcing people into making a decision, within a small window of time, by emphasizing the future unavailability of something. If you give people all the time in the world to make a decision, they will either take up every minute of that time, or never make a decision at all.

The successful application of the scarcity principle in design and marketing campaigns, is preventing users to take time to think about their decision, and instead try to push people into making a decision, immediately. However, it’s a careful balance; stressing users too much will make them run away up front.

Lead users through a predetermined sequence of actions or events, step by step. [...] Guiding users through a process or experience provides opportunities to persuade along the way

Tunneling

Close off detours from the desired behavior, without taking away the user’s sense of control. Tunnel users through a decision process by removing all unnecessary functionality that can possibly distract their attention from completing the process.

Lead users through a predetermined sequence of actions or events, step by step. When users enter a tunnel, they give up a certain level of self-determination – once they have entered the tunnel, they have committed to experiencing every twist and turn along the way.

Guiding users through a process or experience provides opportunities to persuade along the way. The tunnel provides opportunity to expose users to information and activities and ultimately to persuasion.

Give users a piece of the action up front

Allow users to access a limited set of features, functionality, or content without an account. As a consequence of interacting with your product, it is natural for users to give up information about themselves or the context, why the distance to actually creating an account becomes shorter and shorter. The traditional approach is requiring Account Registration, but Lazy Registration help build up users’ investment and Endowment.

It is easier than you think to deliver value to your users without signing in. Some options include: limited content, limited time trials, limited capacity, drafts, and guest checkouts.

Some of the most common design metrics are registered users or paying users. If you share these goals, you do want to prompt users for conversion at some point, but make sure that point is after you have delivered value.

Trying to convert users before delivering on value only increases the chances of them leaving you before you get the chance. Don’t let someone into your product and have them realize that all of the features are locked until they sign in; that won’t feel very free. Engage users early into your product and get them past the need to supply their information to register or sign up.

First time use challenge: falling in love with your product

After getting users to sign up for your product, it’s time to give them a good first-hand experience. Your goal is to let users get a grasp of all your product has to offer. Let us take a look at what you can do to let users experience the true value of your product.

How do we make specific behavior occur?

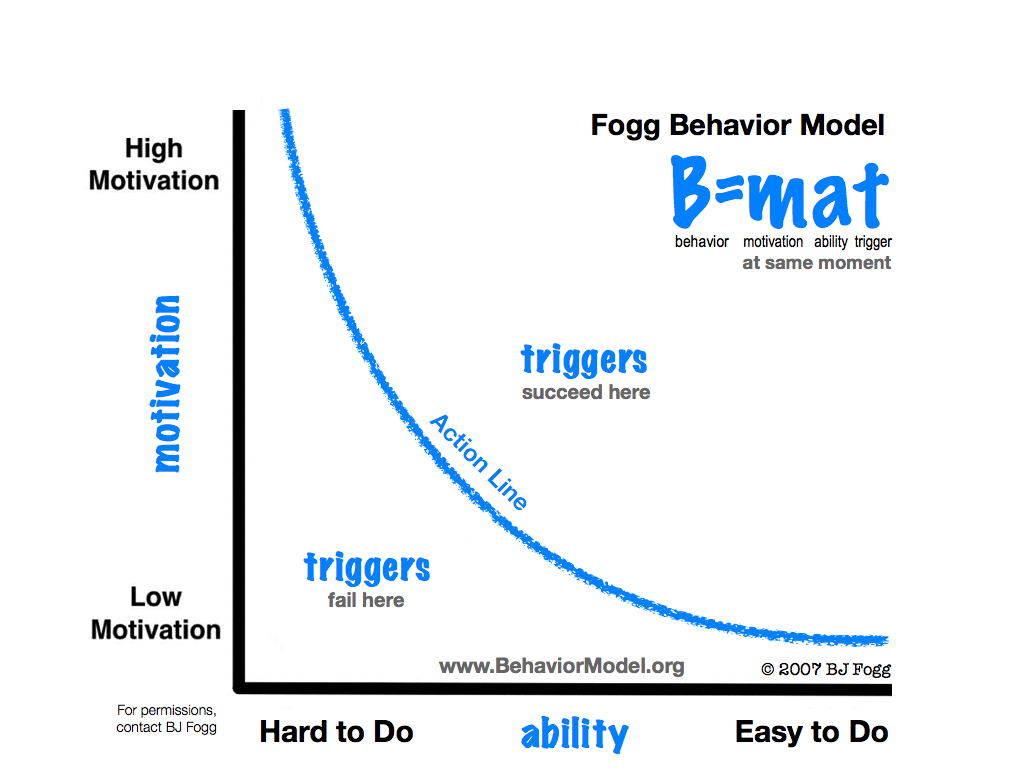

Your aim is to get your users perform the behavior that shows them just how much value your users can potentially receive from using your product. The Fogg Behavior Model explains how three elements must converge at the same moment for a behavior to occur: Motivation, Ability, and Trigger. When examining why users aren’t doing what we intended them to do, at least one of those three elements is missing.