Whether you are helping your users establish habits, engage in something new or unknown, onboard, or just want to motivate your users into giving your product a try, the Fogg Behavior Model can guide you.

About BJ Fogg

BJ Fogg is a Behavior Scientist and founder of the Behavior Design Lab (formerly the Persuasive Technology Lab – Captology) – at Stanford University in California. Fogg has been researching the area of behavior change since the beginning of the millennium. BJ Fogg has summed up some of his most practical and popular findings on how to change behavior into his Fogg Behavior Model.

In 2002, BJ Fogg published one of the first books on Persuasive Design called Persuasive Technology. He further explains his Fogg Behavior Model in his 2020 book, Tiny Habits: The Small Changes that Change Everything.

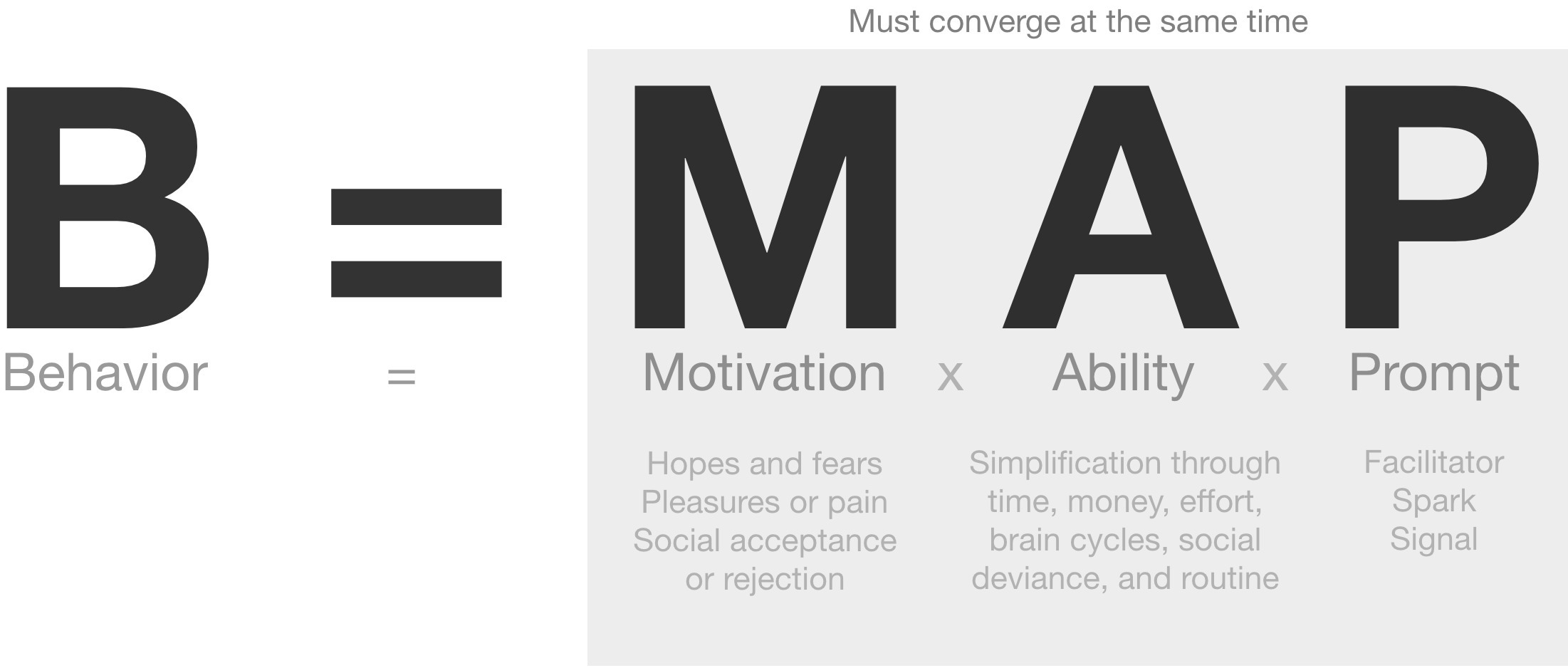

Simply stated, the Fogg Behavior Model states that any behavior will only happen when three elements converge at the same moment in time. These three elements are:

- Motivation. Your users are sufficiently motivated to engage in the behavior.

- Ability. Your users are able to perform the behavior.

- Prompt. Your users are prompted at the right time to perform the behavior.

Even though the model is fairly straightforward and easy to understand, that isn’t necessarily the case for applying it to real life situations. In this article, I’ll explain the Fogg Behavior Model, but while doing so, I will explain specifically which persuasive techniques you can use for each of the three elements.

The Fogg Behavior Model,

B = MAP, explained

Fogg suggests three things need to converge at the same moment in time for behavior to happen: Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt. If a behavior does not occur, at least one of those three elements is missing.

The BJ Fogg Behavior Model shows us that behavior is the result of three specific elements coming together at one moment in time. B=MAP.

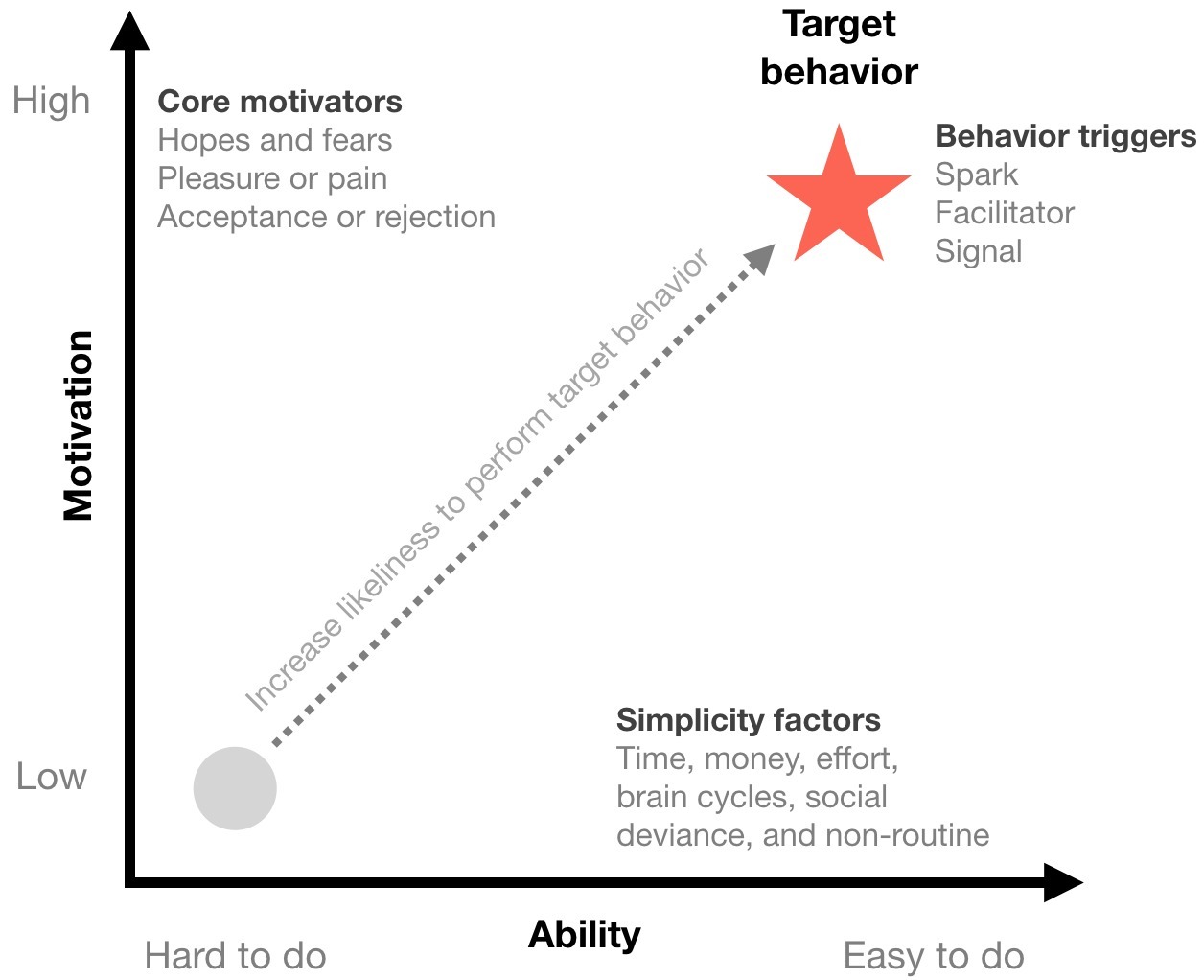

For a user to perform a target behavior, increasing his or her motivation or ability to do so will increase the likelihood of the behavior happening. Secondly, for behavior to occur, it needs to be prompted.

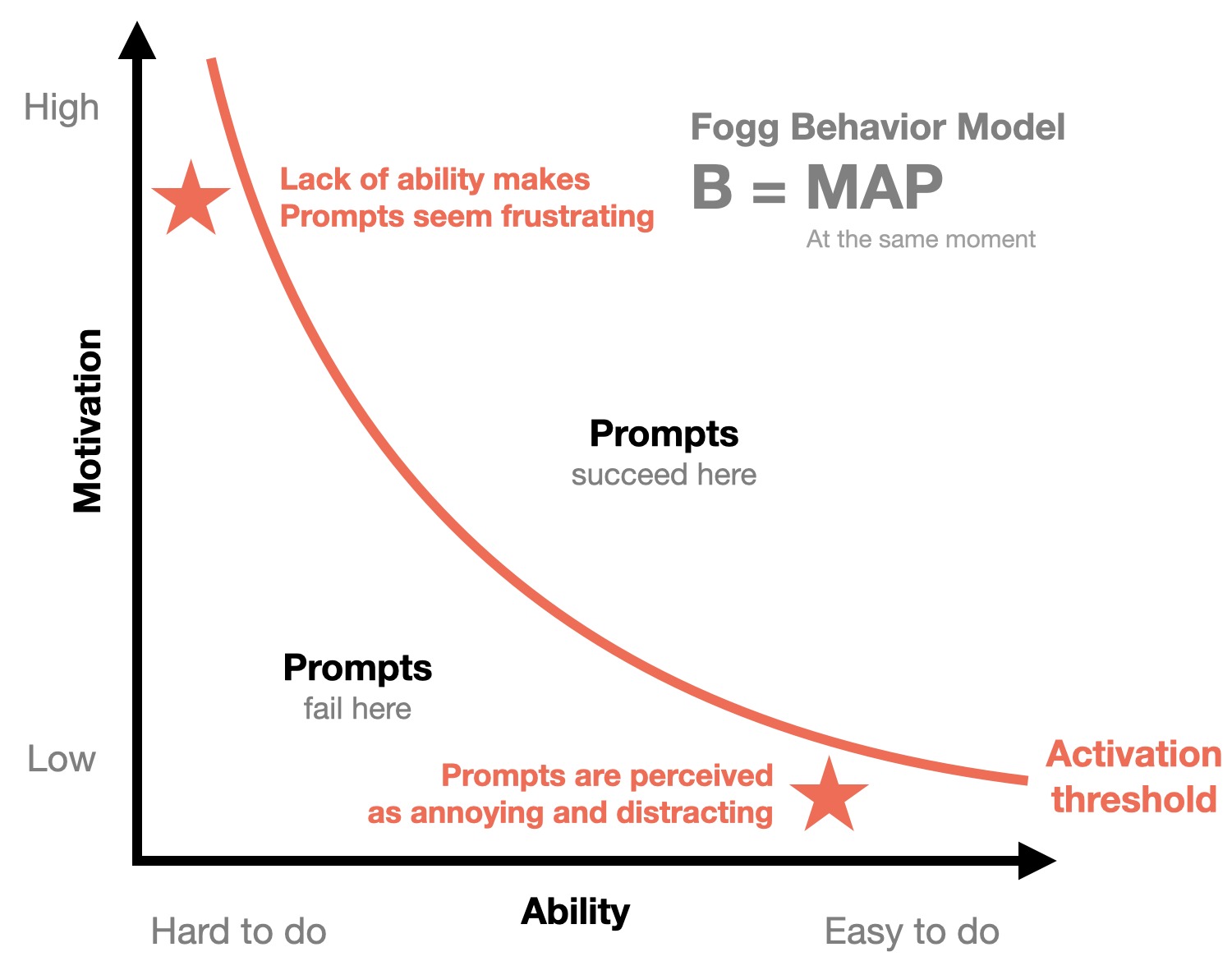

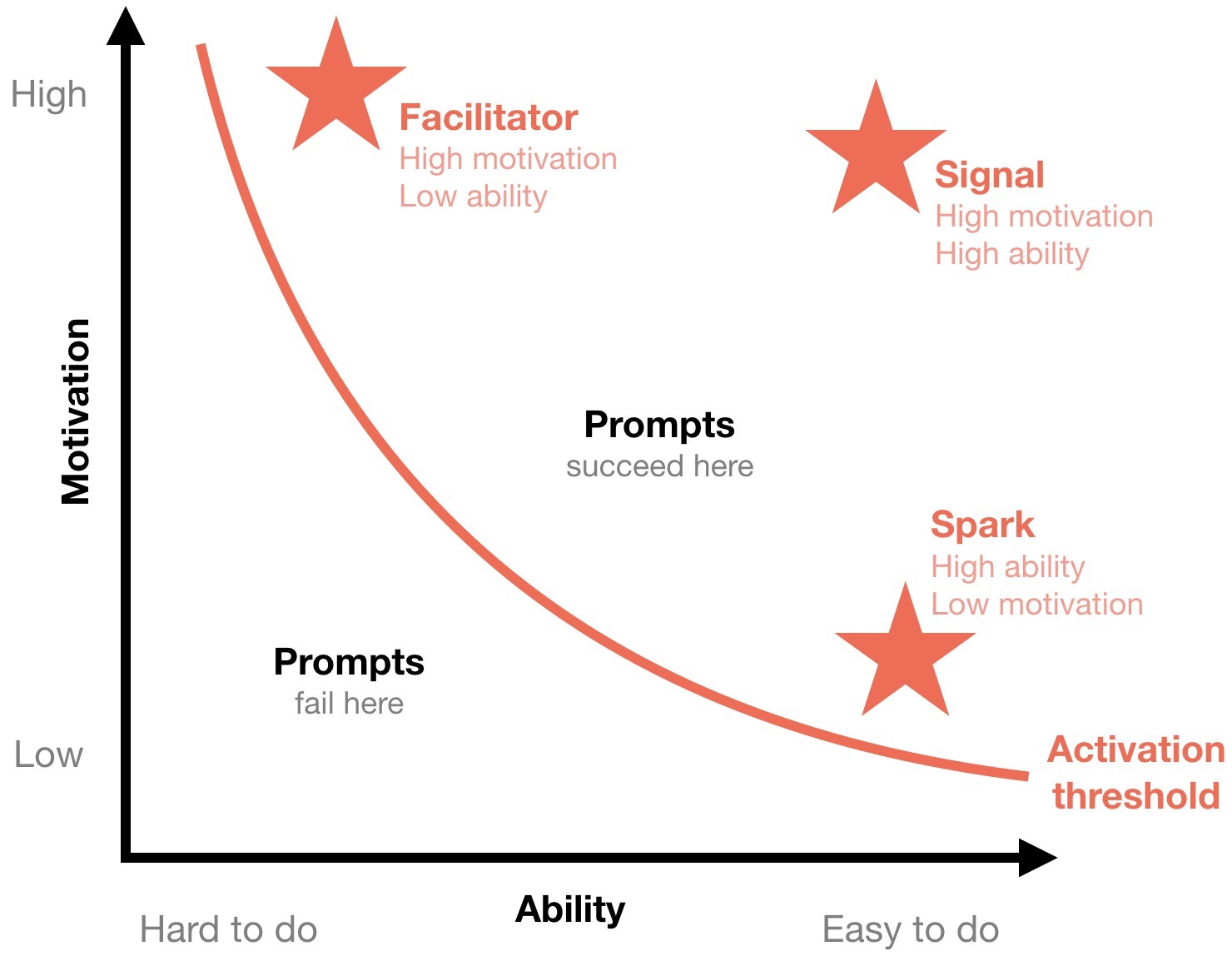

Lastly, Motivation and Ability can be traded off. That is, if motivation is very high, ability can be low, and vice versa. In the Fogg Behavior Model, Motivation and Ability have a compensatory relationship to each other illustrated by the curved line representing an activation threshold in the figure below.

When a combination of motivation and ability places a person above the activation threshold, then a prompt will cause that person to perform the target behavior. If a person is placed below the activation threshold, then a prompt will not lead to the target behavior.

Digital products often do a bad job of prompting behavior. Spam, pop-ups, and ads are actual prompts, but rarely convert to behavior on cue as we have a low motivation to do what the prompt says. Instead, email alerts, bouncing icons, and notifications become annoying and distracting.

When we are ready to perform a behavior, a well-timed prompt is welcome. It isn’t when out motivation is low for that specific behavior. Then it’s distracting. In reverse, when we do want to perform a prompted behavior, but lack the ability, we feel frustrated.

Before going into detail on well-timed prompts, let’s examine the prerequisites on what makes prompts work: sufficient motivation and ability to perform a behavior in the first place.

Influencing the subcomponents of behavior change

Influencing Motivation

BJ Fogg identified three core motivators in his behavior model, the underlying drives which motivate us as humans: sensation (physical), anticipation (emotional) and belonging (social). Influencing each of the three drives underlying drives requires different measures.

Sensational motivation: we seek pleasure and avoid pain

Gamification has been successful in quantifying the outcome of our actions to make users feel either pleasure by achievement and obtaining closure – or pain by not achieving our goals. Mechanisms such as Badges, points, and leaderboards make it easy for users to gauge their status and progress toward a goal they hope one day will give them pleasure achieving. Several concept can be utilized to quantify the user experience to let users feel and discover pleasure or pain:

- Achievements. We tend to engage in behavior in which meaningful achievements are recognized. Consider how you are currently linking desired behavior to achievements.

- Goal-Gradient Effect. Having closure is a reward in itself. Our need for closure and completion drives us toward action, so find ways to anticipate celebration of completion to engage users in your target behavior.

- Levels. Using levels to communicate both progress and future goals is a great way to keep the skill level of users in check as their ability grows.

- Cognitive Dissonance. When we are psychologically uncomfortable, we are motivated to resolve conflict in order to reduce the dissonance.

- Revenge. When we feel unfairly treated, we have an urge to want everyone else to know what happened to us and retaliate.

An experienced pain can be as motivating as an experienced pleasure. In fact, behavioral economics suggests that the emotional negative value of a monetary loss of $100 is at least twice as big as the emotional positive value of a monetary gain of $100. This phenomenon is explained by the Value Function in Prospect Theory by Kahnemann and Tversky1.

Drawing further from the field of behavioral economics, several concepts can be applied to increase motivation to engage in a specific behavior:

- Loss Aversion. Our fear of losing motivates us more than the prospect of gaining something of equal value.

- Endowment Effect. Possession feels like ownership, so when we possess something, we feel that it would be a loss to let go – even though we don’t own it.

- Framing. We tend to avoid risk when a positive frame is presented to us, but tend to seek risks when a negative frame is presented.

- Anchoring. When making decisions, we often rely proportionally more on the first piece of information offered to us.

- Status Quo Bias. We tend to accept the default action instead of comparing the actual benefit to the actual cost.

- Sunk Cost Bias. We have a tendency to continue to invest, even if it brings us losses, as we hate to see our initial investment go to waste.

Anticipatory motivation: our hopes and fears influence our emotions

According to BJ Fogg, hope is the most ethical and empowering motivator. Motivating through hope talks to our innermost intrinsic motivations: our desire to do or be part of something that matters. Hope is being part of something meaningful or the anticipation that what you are about to engage in leads to something meaningful. This feeling can be facilitated through mastery by providing a sense of purpose by recognizing a job well done or simply enjoying a job well done. Several tricks can be used to cater to our intrinsic hopes and fears.

- Storytelling. The narrative qualities of stories help users engage in a different perspective than their own.

- Autonomy. We feel autonomous when we feel as if we have control over our own destiny. The feeling is reinforced when that freedom is not granted to everyone.

- Curiosity. We crave more when teased with a small bit of interesting information.

- Achievement of a learning goal. People who manage to set goals typically achieve more than when their goals have been set by someone else (typically a teacher).

Similarly, fear, the anticipation of something bad happening, often a loss, will equally motivate us toward action. Just as the hope of gaining a future reward can motivate us to act, so can the fear or not obtaining it. It’s a matter of framing and perspective. All rewards and possible achievements can be framed as something we stand to gain or as something we stand to lose.

Scarcity is often used as a tool to frame a future gain as something negative. By framing something as being less attainable or accessible, its perceived value rises.

Social cohesion: we seek social acceptance and avoid social rejection

As humans, we strive to feel accepted – as if we belong. Similarly, we try to avoid feeling rejected2. We are motivated to act, when we can win social acceptance and status just as we are motivated to avoid negative consequences which might lead to social rejection.

A number of persuasive patterns seek to motivate users to act by influencing our sense of belonging:

- Reciprocation. We feel obliged to give back when we receive something.

- Liking. People respond not only to the message, but also to the messenger. That’s you.

- Social Proof. When we are in new and unfamiliar situations (socially or not), we assume the actions of others to feel safe.

- Status & Reputation. We tend to adjust our personal behavior to reflect positively on how peers and the public see us

- Nostalgia Effect. Reminiscing about the past and the social connections we have had, we tend to favor social connections and downplay economic costs.

Influencing Ability

Ability refers to the ease of which a specific behavior can be performed – the skill level required. The obvious approach to making sure a user possesses the necessary skill-level to perform a behavior is to make sure that it represents an Appropriate Challenge, as described with the Flow Channel by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

We have examined how we can influence whether a target behavior occurs. The other side of the equation is ability.To perform a target behavior, a person must have the ability to do so. There are three ways to increase the ability to perform a behavior:

- Train people to increase their ability. Give people more skills (more ability) to do the target behavior. This approach to increasing ability is hard and is quite an investment, so only take this path if you must. Training people comes with the risk that most people resist learning new things, as we as humans are inherently lazy.

- Provide a tool that makes behavior easier to do. A second route is to give people tools or resources that make the target behavior easier to do. A cookbook makes cooking a home easier to do and an electric screwdriver makes it easier to screw.

- Scale back target behavior. Work with people to scale back their ambitions and save the difficult behavior (such as stop smoking or weight loss) for later projects – after they have learned to succeed at more manageable behavior changes. Break down big habit changes into a series of tiny habits to make sure that a change in the right direction happens.

Increase Ability through higher simplicity

The simpler a behavior is to perform, the higher our ability will be. By focusing on simplicity of the target behavior you increase Ability. Ensure that users possess a sufficiently high skill by making the target behavior as easy to perform as possible: to simplify the behavior. Nobody will do anything they don’t think is worth the effort, why making a task simpler is a great way to encourage new behavioral patterns to stick.

Simplicity is a function of your scarcest resource at that moment

Simplicity is a function of your scarcest resource at that moment.

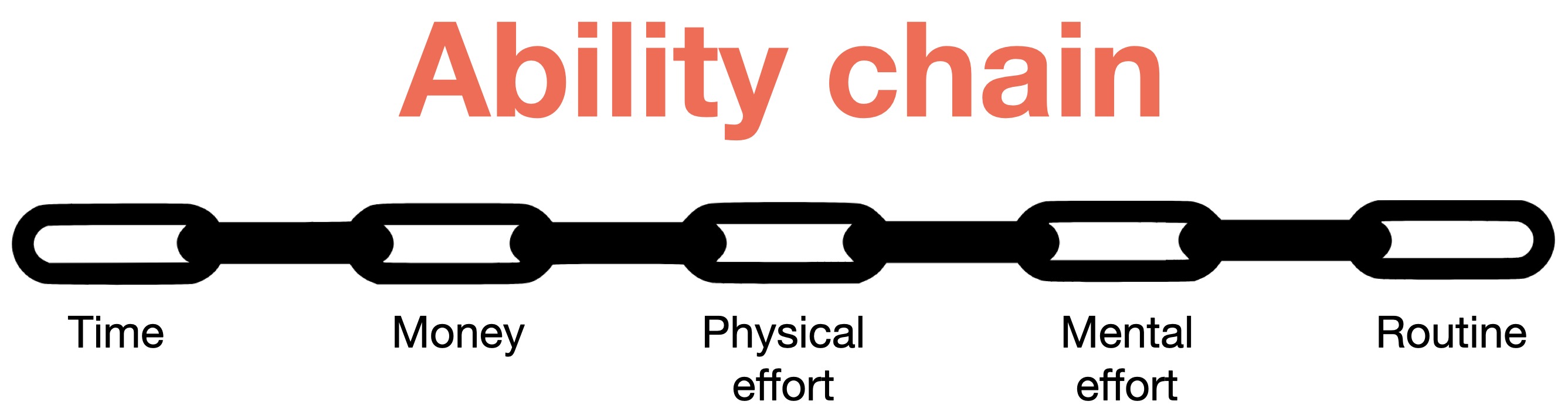

Find the weakest link by asking: “What factor makes this behavior difficult?” Difficult refers to any amount of friction that is holding back people from doing their target behavior. Often our perception of the difficulty is more important than the actual difficulty of an activity.

Once you have found the weakest link in the ability chain, strengthen it by asking: “How can I make this easier?”. Answers to this question should be based in the person, in the action, or in the context.

Your weakest link determines what makes a behavior hard to do.

Your weakest link determines what makes a behavior hard to do.

Think about time as a resource. If you don’t have 10 minutes to spend, and the target behavior requires 10 minutes, then it’s not simple. Money is another resource. If you don’t have $1, and the behavior requires $1, then it’s not simple.

Fogg outlines six ways a task can be made simpler: time, money, physical effort, brain cycles, social deviance, and non-routine.

Limit time to make behavior simpler to perform

If a target behavior requires our time, but we do not have time available, then the behavior is not simple. If the target behavior is to fill out a registration form with 100 fields, then that behavior is not simple for me because I usually have other things more worthwhile to do.

There is a significant persuasive effect in simplifying behavior:

- Limited Choice. It is much easier for us to make a decision, when there are fewer options to choose from.

- Tunneling. Close of detours from your desired behavior without taking away the user’s sense of control.

- Tailoring. Tailored information is more effective in motivating behavior as there is less irrelevant information for the user to filter.

- Powers. Provide users a way to reach their goal more quickly than they could before.

- Unlock Features. Unlock new features as a reward for specific behavior.

- Feedback loops. Make it easier for users to adjust their behavior and future actions by providing prompt feedback as they interact.

While creating products that actually save users time is always be preferable, there are a number of persuasive design techniques that will decrease perceived time consumption:

- Chunking. It is easier to process and remember information when it is grouped into familiar and manageable bits.

- Sequencing. When complex activities are broken down into smaller bits, it is easier for people to start engaging in that behavior.

- Serial Positioning Effect. It is easier to recall the first and last elements in a list.

Limit the brain cycles we need to use to reduce cognitive load

As humans, we hate to think. We have a limited cognitive load, the amount of mental effort being used in our working memory, and being forced to think too hard in turn reduces our processing fluency, the ease with which we process information. If performing a target behavior causes us to think hard, then we don’t see the behavior as simple, as it hurts our processing fluency.

If we in one way or the other can get away with not spending brain energy, we will try to do so. For the most part, we as designers overestimate how much everyday people want to think.

Limiting choice, tunneling, tailoring, chunking, sequencing, and using the serial positioning effect discussed earlier in regards to limiting time spent, all work to minimize our cognitive load. There are however even more applicable tricks from persuasive design we can use to increase the user’s processing fluency and limit the cognitive load:

- Priming Effect. It is easier for us to access particular items in our memory, when we have recently been exposed to related stimuli.

- Recognition over Recall. We are better at recognizing things from a list than we are recalling them from memory.

- Intentional Gaps. We are motivated to complete the incomplete, the closer to completion a task is.

- Isolation Effect. Items that stand out from their peers are easier to remember.

- Conceptual Metaphor. It is easier for us to understand a new idea or concept, when it is linked to another more familiar concept.

- Reduction. Simplify complex behavior to increase the benefit/cost ratio, making it easier for users to engage in the target behavior.

Money can both complicate and simplify target behavior

If your users have limited financial resources, a target behavior that costs money is not simple. However, it is a trade off: wealthy users will simplify their lives by using money to save time.

Limit the physical effort needed

When a significant amount of physical effort is required before a target behavior can be performed, then it is not simple to do. If switching from one desk to the other with my computer requires unplugging and plugging in a bunch of cables, then that is less simple than just switching to a similar docking station. Going to my office by bike seems simpler than walking the same distance.

We don’t like to be social deviant

Accepting the norm and following the lead of others is simple behavior as we then avoid thinking too hard. Going against the norm, breaking the rules of society, creates complications for a target behavior. Wearing pyjamas to a client meeting may require little effort, but I would have to pay with my social pride.

As we most often learn from the behavior of others, highlighting socially deviant actions of others or simulating a socially deviant behavior, can make performing a socially deviant behavior seem simpler.

- Social Proof. Social Proof establishes the norms of which others follow.

- Positive Mimicry. When learning new things, we tend to automatically imitate other people’s behaviors. Make it easier for users to engage in behavior, by first showing how other people are conducting similar behavior.

- Role Playing. How we act depends on the social norms of the context we are in. Can you modify the context, so that conducting unfamiliar behavior seems natural?

Non-routine

We find routine behaviors simple, as we do them over and over again. When we as humans face a behavior that is not routine, then in many cases, we won’t find it simple. As we seek simplicity, we often stick to our routine; buying groceries from the same shop or gas at the same station – without comparing the actual benefits to the actual costs.

A few persuasive design techniques can be used to make non-routine behavior seem less frightening, providing prompt feedback that we are on the right path toward behavior change.

- Simulation. Enable users to observe the link between cause and effect in real time.

- Self-monitoring. Make it easy for people to know how well they are performing a target behavior.

The power of simplicity

Each person has their own individual simplicity profile. While some people have more time, others have more money. While some can invest brain energy, others can’t.

These factors vary by the individual, but also depend on the context. For example, if my bike is stolen, it is no longer simple to travel to my work location, as I’m then traveling by foot.

Fogg states that simplicity is a function of a person’s scarcest resources at the moment a behavior is prompted5. As designers, we should seek to discover what resources are most scarce for our audience at the time a behavior is prompted: time, money, or ability to think? When we have discovered what the scarcest resource is, we can start to account for BJ Fogg’s six factors of simplicity and start reducing the barriers for performing a target behavior.

In general, Persuasive Design succeeds faster, when we focus on making behavior simpler instead of trying to pile on new motivational factors. As humans, we often try to resist attempts at motivation, but naturally engage in simple tasks.

Influencing with prompts

Without an appropriate prompt, behavior will not occur. Even if both motivation and ability are both high. Timing is key. When we are ready to perform a behavior, a well-timed prompt is a welcome distraction.

Successful prompts generally have three characteristics:

- We notice the prompt. If we don’t notice the prompt, we can’t act on it.

- We associate the prompt with a target behavior. Otherwise, how would we know what to do?

- The prompt is fired as we are both motivated and able to perform the behavior. Otherwise we will be annoyed or frustrated.

Lastly, there is timing. The opportune moment to act is any time motivation and ability place people above the activation threshold.

A prompt is something that tells people to perform a specific behavior. It typically goes by the name of call-to-action, notifications, prompts, etc. However, not all prompts perform in the same way. Fogg outlines three different kinds of prompts: sparks, facilitators, and signals.

BJ Fogg outlines three types of prompts, facilitators, sparks, and signals.

A spark motivates behavior, a facilitator makes behavior easier, and a signal indicates or reminds users.

Spark prompts

In situations where users have the ability, but lack the motivation, highlighting fear or inspiring hope are effective means. Leveraging the power and corresponding persuasive patterns of any of the three core motivational drives mentioned earlier (sensational, anticipatory, and social cohesion) will do the trick.

Powerful spark prompts could be:

- Periodic Events. Construct recurring events or traditions to build up anticipation.

- Fresh Start Effect. We are more likely to achieve goals set at the start of a new time period.

The chosen channel or form does not matter as much as the prompt is recognized, associated with the target behavior, and is presented to users at a moment, when they are able to take action.

Facilitator prompts

In situations where users have a high motivation, but lack ability, facilitation is an appropriate strategy. When facilitating prompts are effective, they convey to users that the target behavior is easy to do and that it will not require resources he or she does not already have.

Signal prompts

In situations where users have both high motivation and high ability to perform a target behavior, a signal, for instance a simple reminder, is enough. As opposed to facilitator- and spark-prompts, it is not necessary for the signal-prompt to motivate or simplify a task. The signal merely services as a reminder. An everyday example could be a traffic light: A traffic light doesn’t need to motivate me to drive, it simply indicates that now is a good time to do it.

Powerful prompts

As our digital devices become more context aware, the more powerful prompts have the potential to be. As recipients, we will be most tolerant of signal- and facilitator-prompts, as spark-prompts have the potential to annoy us by being an unwelcome distraction as they try to motivate us to something we have no original intention of doing.

Motivation matching and motivation waves

You can’t simply layer motivation on top of something you want people to do. How your users are going to be motivated to perform a specific behavior shouldn’t be an afterthought.

Instead, you pick specific behaviors that your users already want to do. Those behaviors help them achieve an outcome or result they already want. It’s not that motivation doesn’t matter, but you shouldn’t tack it on at the end. You need to match your own behavioral goal as a business (or how you frame what you want them to do) with what they already want to do.

Coming back to what BJ Fogg said, motivation has only one role, to make hard things easier, it’s not that motivation doesn’t matter. But you don’t simply layer motivation over something you want people to do. As BJ Fogg puts it, you have to be motivation matching. What you are trying to motivate needs to match what people already want to do. But sometimes you have cases in which you do have to insert motivation into the situation to get people to do something.

The right time to motivate

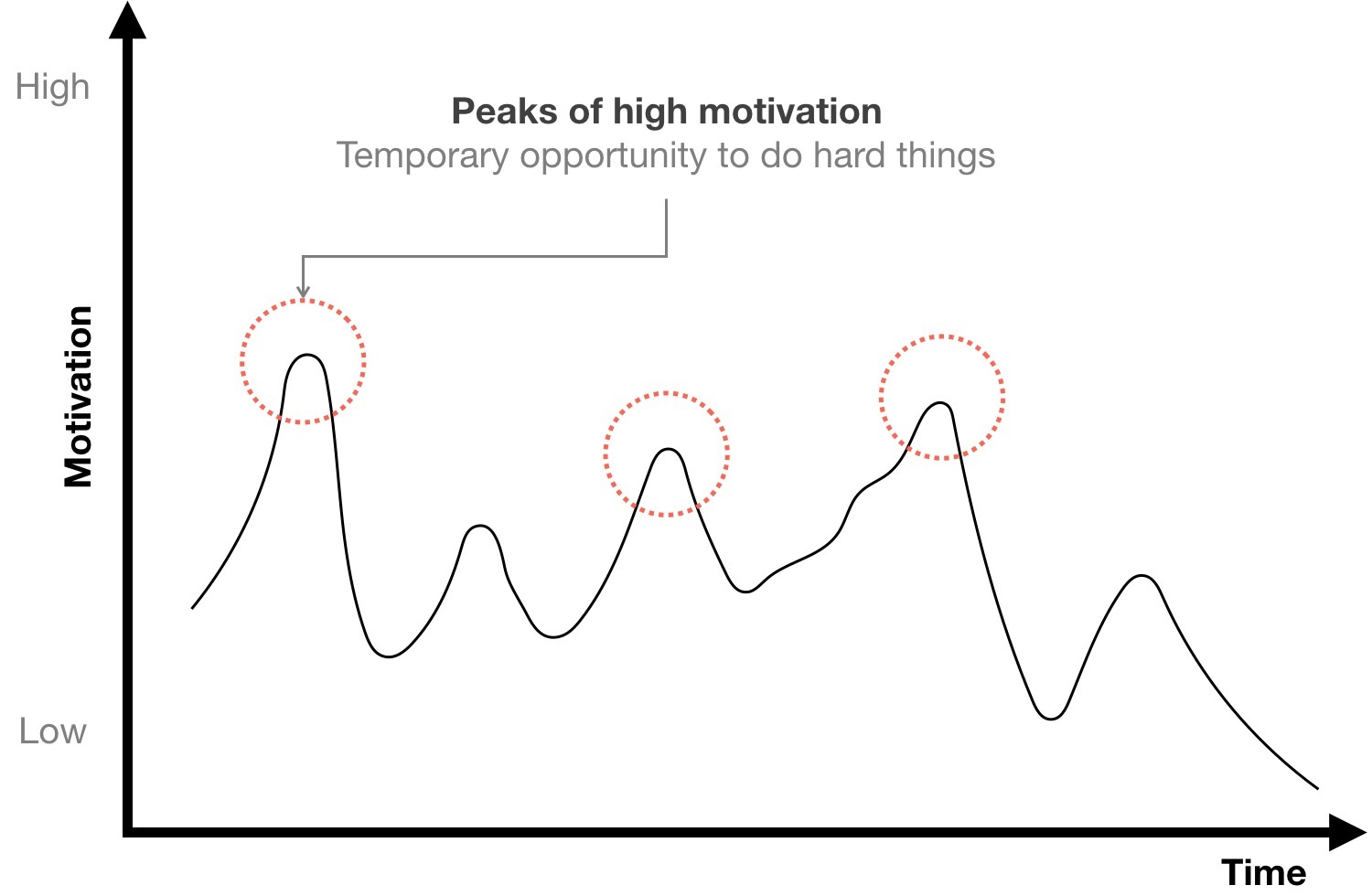

In our lives, we have all experienced moments, in which we have peaks of motivation. Peaks happen when we get excited about something.

Motivation comes in waves as we get excited about different things in different contexts

It could be about something good, for example when we watch sports on TV and get the inspiration to go out and start doing sports ourselves. Motivation can also come in the shape of something bad happening: a natural disaster would make us prepare for what is to come and a breakup could motivate us to get back in shape.

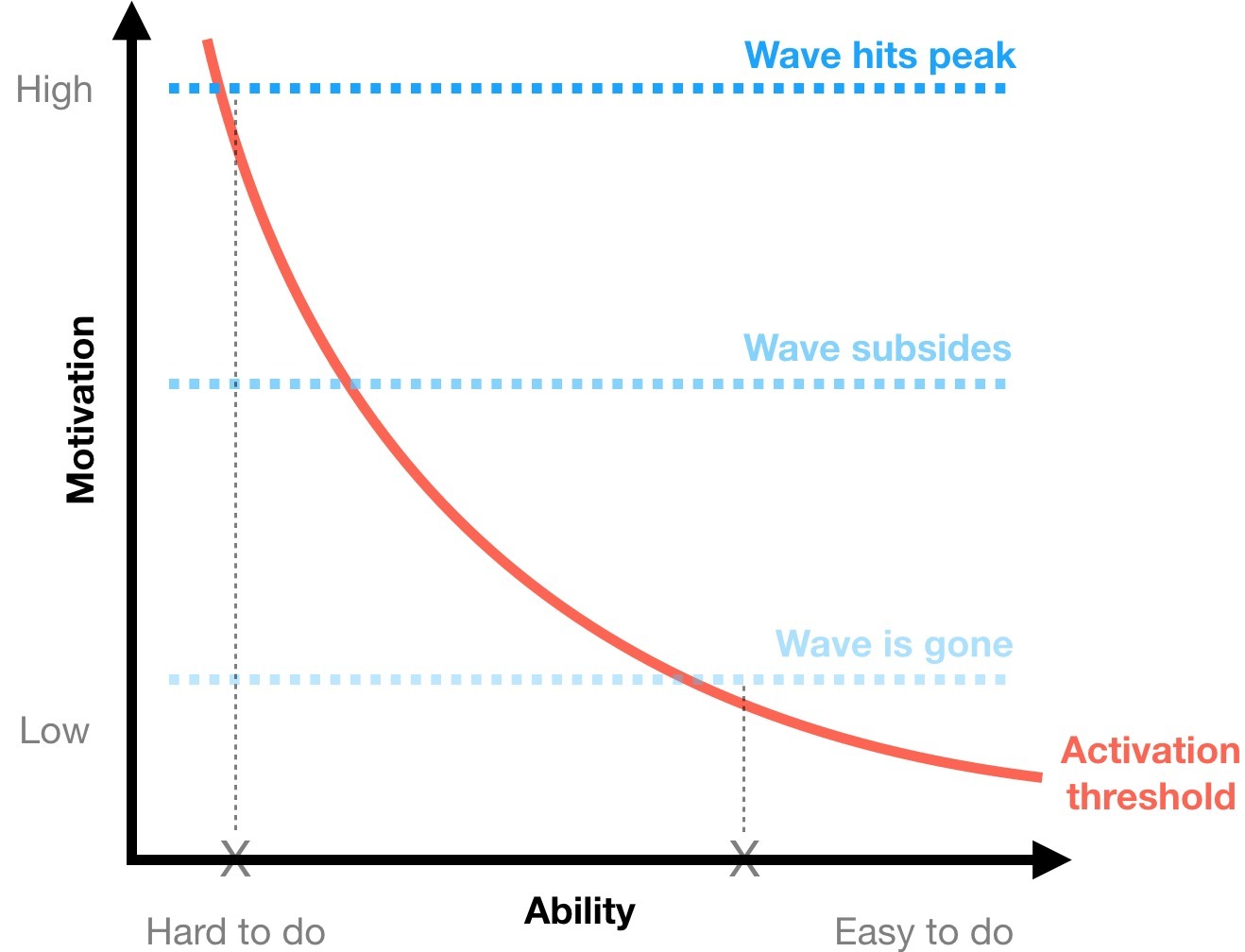

When a motivation wave is upon us, we can do harder things than when the wave has subsided.

During those situations, we go into what BJ Fogg calls a motivation wave where we are able to do harder things. As the wave comes back down and flattens out, and it usually does, we again become less able to do hard things.

When the wave is high, we have a temporary opportunity to do hard things. From a product or business perspective, it means that when your customer is in a motivation wave, that’s the time when you prompt them to do hard things. The strength of a motivation wave is limited in time, so you need to act quickly before the wave subsides. We aren’t always going to be thinking, “I got to get back in shape” or “spend more time with my family”.

Competing behavior and motivation waves

At all times, there will be more than one behavior competing for our attention. Several motivation waves will similarly at all times overlap, each requiring its own different behavior. For example, we can be struck by a motivational wave to get back in shape and start exercising, while at the same time, we get a call from the school your kid goes to, that he or she got hurt. In this case, you would hopefully feel more motivation to pick up your son or daughter from school, than you would going to the gym. At all times, we are choosing between competing behaviors and motivation waves.

Breaking big tasks up into small baby steps, which wouldn’t require as much motivation to perform, is a great strategy for managing to do both. BJ Fogg advocates for building up tiny habits, letting users take baby steps to begin with, simply to lower the needed ability to start a behavior.

Sources

1 Prospect Theory by Kahnemann and Tversky

2 Fogg Behavior Model by BJ Fogg

3 Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

4 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi at Wikipedia

5 A behavior model for Persuasive Design by BJ Fogg

6 Proccesing fluency at Wikipedia

7 Fogg Behavior Model: Surfing the behavioral wave at Fora.tv

8 Motivation: explained by BJ Fogg by Astrid Groenewegen

9 5 Factors for Success: The Tiny Habit’s Ability Chain by Hannah Aster

10 Fogg, BJ (2009). A behavior model for persuasive design, Persuasive ’09: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology. Pages 1–7

11 Fogg, BJ (2009). Creating Persuasive Technologies: An Eight-Step Design Process. Persuasive Technology, Fourth International Conference, PERSUASIVE 2009, Claremont, California. Proceedings

12 How Using the Fogg Behavior Model Increases Clicks & Sales by Paul Boynton

13 BJ Fogg Behavior Model: B=MAT Extended by Yu-kai Chou