Liking

Design Pattern

Problem summary

We prefer to say yes to the requests of someone we know and like

Example

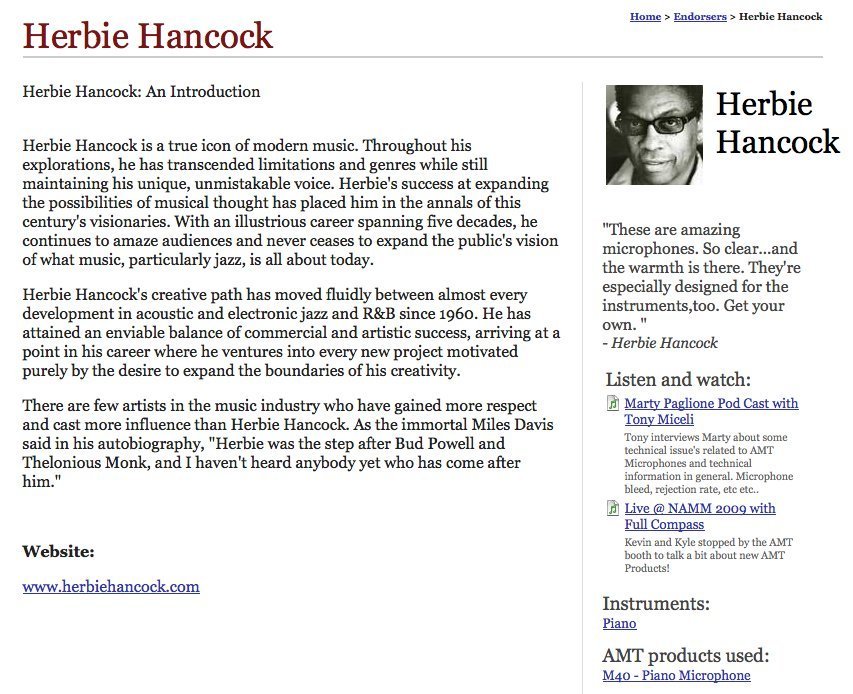

▲ The specialized instrument microphone company, "Applied Microphone Technology" spends large amounts of energy and money to endorse famous and respected artists who use their product. This is an attempt let the liking of the endorsed artists fall back on the microphone company because of the association.

Usage

- Use when you represent an authority figure who your users know or like

- Let your users express themselves and their opinions to their friends through invitations, comments, reviews, recommendations, and other gestures.

- Use to increase likelihood of strangers complying to your requests.

This card is part of the Persuasive Patterns printed card deck

The Persuasive Patterns Card Deck is a collection of 60 design patterns driven by psychology, presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!Solution

Liking of you and your products depend on a series of things. Those listed below are summed up from Cialdini’s book: Influence1.

- Physical attractiveness

- Similarity

- Compliments

- Contact

- Cooperation rather than competition

- Conditioning & association

Physical attractiveness

It is generally acknowledged that good-looking people have an advantage in social interactions. A sort of halo effect occurs when one positive characteristic of a person dominates the way that person is viewed by others. Research has shown that we automatically assign favorable traits as talent, kindness, honesty, and intelligence to good-looking people1. The same is true for a good-looking product. Attractive things work better2. As does good-looking web design.

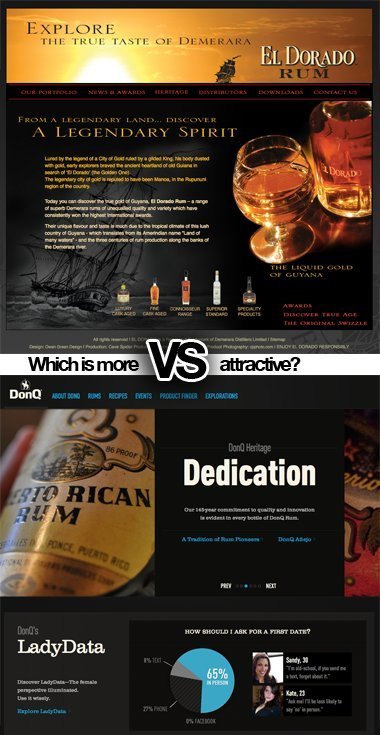

Which is do you think is more attractive? The website of Demerara – Eldorado Rum or the website of DonQ Rum? We assign favorable traits to attractive things and look past less attractive traits. Research has shown that attractive things clearly work betterwork better2!

Similarity

We tend to favor people with similar backgrounds and interests. Find a way to either assure your users that you are like them, or that your users are similar to them. Testimonials from people with the same problems, backgrounds, or interest can help spark liking you.

Corkd.com explains why you should sign up by saying “interact and share with your drinking buddiesâ€. You can interact about wine with people of similar interests (wine).

Compliments

We are big suckers for flattery. Even when we are completely aware that its impersonal, clearly false, and designed only to convert us, we tend to believe praise and to like those who provide it. Compliments and praise automatically produces a positive reaction that makes easily makes us fall victim to obvious attempts to win our favor1.

We are suckers for flattery. As people like our posts on facebook and we get more followers on twitter, we feel motivated to write and ourselves engage more to receive even more flattery.

Contact

Contact between people who would normally dislike each other can increase likening and understanding between the two, depending on the experience. A positive experience leads to a higher familiarity and liking while a distasteful one produces the opposite effect.

Mass chat communities like those generated by IRC has brought people together that would normally never get a chance to talk. Even though the chat might not have been about breaking down boundaries, meeting and talking to people not similar to ourselves increase our liking of the group those people represent.

Cooperation rather than competition

We like people and things that are familiar to us or seems like us, as we can identify with them. We also have a tendency to dislike people and things that are not familiar and do not seem like us.

Once competition between people starts, this effect is enhanced. Competition makes us stick with what we know and distance ourselves from what we don’t.

Cooperation on the other has a dampening effect. Cooperation with people who are not like us can help us like them more. Even a vague understanding of a cooperation taking place will help. Use cooperation to increase liking between groups that a far apart. Point out cooperation in a situation when it exists naturally. Amplify cooperation when it exists only weakly. Try to manufacture it when it is absent. Can you create a feeling of “us against the system”, that we “pull together” for mutual benefit, or that you work together with your users to get them to kick ass?

On the other hand, competition can help companies make you dislike their competitors, and make you love their own company more.

Apple’s Mac vs. PC campaign played on the long-time rivalry and competition between Macs and PCs. It helped start and spark a bond between Mac owners that PC owners never had – a connection with one simple Apple-favored message: PC is bad, Mac is good. Brilliant execution!

Conditioning & association

We have a tendency to try to bask in reflected glory by what and who we associate and connect ourselves with. We try to connect ourselves to success by using the pronoun “we” and distance ourselves from losers by using “they”. It works. Connect yourself or your products with things your users like to increase liking.

The specialized instrument microphone company, “Applied Microphone Technology” spends large amounts of energy and money to endorse famous and respected artists who use their product. This is an attempt let the liking of the endorsed artists fall back on the microphone company because of the association.

Rationale

People respond not only to the message, but the messenger, and that’s you. Being likable attracts. Being unlikable repels. Demonstrate a positive attitude. Be positive rather than negative, and encourage rather than criticize.

We are receptive towards messages from what and who we like to such and extend that facebook designed one of its key features around this: fan pages. You can choose to “like” a fan page and in turn subscribe to posts from that page. It is a feature both popular among users but even more popular among fan page owners, as it leverages the very persuasive principle of Liking1.

We respond much more favorably to people and things we like and know than those we either do not like or are not familiar with. This fact can be used to increase the likelihood of strangers complying to your requests.

When a stranger tells us that a friend of ours suggested we could help, we have a hard time rejecting the person – even though he or she is a total stranger. Turning away a person under those circumstances is difficult – it’s almost like rejecting the friend!

We are quick to point out flaws of political candidates of the opposition, but have a tendency to look through failures of who we root for. The more we like people and things, the more open we are to complying with what they communicate.

Discussion

The “Liking” pattern draws heavily from the principle of affiliation and attraction in psychology, which posits that humans have a fundamental drive to bond with others and are more inclined to be influenced by people or entities they find appealing.

At its core, the Liking pattern capitalizes on the basic human inclination to trust, listen to, and be influenced by those we like or have positive feelings towards. This can be due to several factors, such as shared interests, physical attractiveness, compliments, or perceived similarities. The principle implies that if an individual or brand is perceived as likable, their messages or offers are more likely to be received positively and acted upon. However, it is essential to recognize the responsibility that comes with this power of influence. Misusing it can lead to mistrust and can be ethically questionable. Authenticity and genuine intent are crucial components to ensure the ethical application of the Liking pattern.

One of the most effective ways to cultivate liking is by establishing common ground. For digital products, this can translate to creating user interfaces that resonate with the user’s preferences or cultural backgrounds. This familiarity breeds comfort. For instance, if a platform identifies that a user has a penchant for a particular genre of music, it might display recommendations from that genre more prominently.

Personalization is another powerful tool. By tailoring user experiences based on previous interactions, designers can make users feel understood and valued. When a user feels a product “knows” them, they inherently develop a liking for it. Imagine a fitness app that not only tracks a user’s progress but also celebrates milestones with them, reinforcing the shared journey.

While the “Liking” pattern is influential, it’s crucial to navigate its application judiciously. A common pitfall is over-personalization, where users might feel their privacy is being invaded. While tailoring experiences, it’s essential to ensure users don’t feel like they’re under surveillance.

Another error is assuming that what works for one demographic will work for another. Cultural sensitivities vary, and what’s appealing to one user group might be off-putting to another. It’s essential to conduct thorough user research and avoid making broad assumptions.

Genuine liking cannot be forced. Overly aggressive attempts to make users like a product, such as bombarding them with too many notifications or recommendations, can backfire.

When combining liking with other patterns, ensure that the likable persona or aspect remains consistent. This builds and maintains trust. For instance, if you’re using a friendly mascot to interact with users (like Duo from Duolingo), maintain that mascot’s presence when incorporating other persuasive patterns like achievements or rewards.

Especially when combining liking with authority bias or social proof, ensure that endorsements, testimonials, or influencer partnerships feel genuine. Avoid making it seem like a mere transaction, as this can diminish the liking factor.

Powerful Pairings

The Liking pattern has the potential to be combined with other persuasive patterns for more effective outcomes. Here are a few combinations:

- Liking + Social Proof.Combining the principle of liking with social proof can be powerful. For instance, when brands use testimonials from relatable individuals or influencers whom their target audience likes, it makes the testimonials more compelling. A classic example is Instagram, where users see recommendations based on not just their interests, but also from accounts that their friends and admired personalities follow or like. This combination reinforces trust and amplifies the inclination to explore or buy.

- Liking + Reciprocity.When a brand or individual does something that users appreciate or find value in, the principle of reciprocity kicks in. Pairing this with the liking principle can enhance the overall user experience. For example, when a brand provides a free webinar or workshop, attendees not only feel obligated to reciprocate (perhaps by purchasing a product or service), but if the presenter is likable, the conversion rate often increases. Dropbox’s referral program is a prime example. By giving both the referrer and referee extra storage space, it combines the goodwill generated by giving (reciprocity) with the trust and liking associated with personal referrals.

- Liking + Storytelling.Narratives resonate with humans, and if the story involves relatable and likable characters or narrators, it’s bound to have a more profound impact. Brands that employ storytelling in their campaigns, and pair it with a likable figure or message, often see higher engagement. Brands like Apple often do this by presenting their product stories and innovations through admired personalities or heartwarming narratives.

Always test the combined effects of different persuasive patterns. What works for one audience might not work for another. For instance, the combination of liking, scarcity, and social proof might work exceptionally well for a fashion e-commerce platform, where users see popular, limited-stock items their friends have liked or purchased. However, the same combination might not resonate as effectively on a B2B software solution site.

Ethical Recommendations

The liking principle can be twisted to create a false sense of connection or rapport with users. By artificially crafting a persona or brand image that seems likable, businesses might lure users into making decisions they might not have made otherwise. This artificial likability, when discovered, can lead to a breach of trust.

With the rise of big data and analytics, there’s a temptation to use personal information to tailor messages that exploit the liking principle. For instance, by leveraging data about user preferences, companies might present themselves or their products in ways that mirror those preferences, even if they don’t genuinely align with them.

Relying on seemingly genuine endorsements or testimonials that are, in reality, paid or scripted can be misleading. Users might be influenced by these endorsements, thinking they are genuine expressions of liking, when they’re just marketing tactics.

- Authenticity is key. Always prioritize genuine interactions and authentic presentations. If a brand or product has likable features, highlight them, but don’t invent or exaggerate qualities for the sake of persuasion.

- Transparent endorsements. If endorsements or testimonials are used as part of leveraging the liking principle, ensure they are genuine. If there’s any compensation or incentive provided for these endorsements, it should be disclosed to maintain transparency.

- Respect boundaries. Avoid over-personalizing content to the point where users feel their privacy is invaded. Respect user data and ensure that any personalization is done with the user’s consent and knowledge.

- Educate and Inform. Provide users with the necessary information to make informed decisions. Instead of just leveraging the liking principle to persuade, combine it with factual, helpful information so users understand the basis of their decisions.

1 Cialdini, R. (1993), Influence: Science and practice (3rd edn), New York: HarperCollins

2 Norman, D. (2004), Emotional Design – Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things, Basic Books, New York

3 Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. H. (1978). Interpersonal attraction (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

4 Aronson, E., Willerman, B., & Floyd, J. (1966). The effect of a pratfall on increasing interpersonal attractiveness. Psychonomic Science, 4(6), 227-228.

5 Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press.

6 Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups; a study of human factors in housing. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

7 Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

More examples of the Liking pattern See all 4 example screenshots

User Interface Design Patterns

- Forms

- Explaining the process

- Community driven

- Tabs

- Jumping in hierarchy

- Menus

- Content

- Gestures

- Tables

- Formatting data

- Images

- Search

- Reputation

- Social interactions

- Shopping

- Increasing frequency

- Guidance

- Registration

Persuasive Design Patterns

- Loss Aversion

- Other cognitive biases

- Scarcity

- Gameplay design

- Fundamentals of rewards

- Gameplay rewards