Anchoring

Design Pattern

Problem summary

We tend to rely too heavily on the first information presented

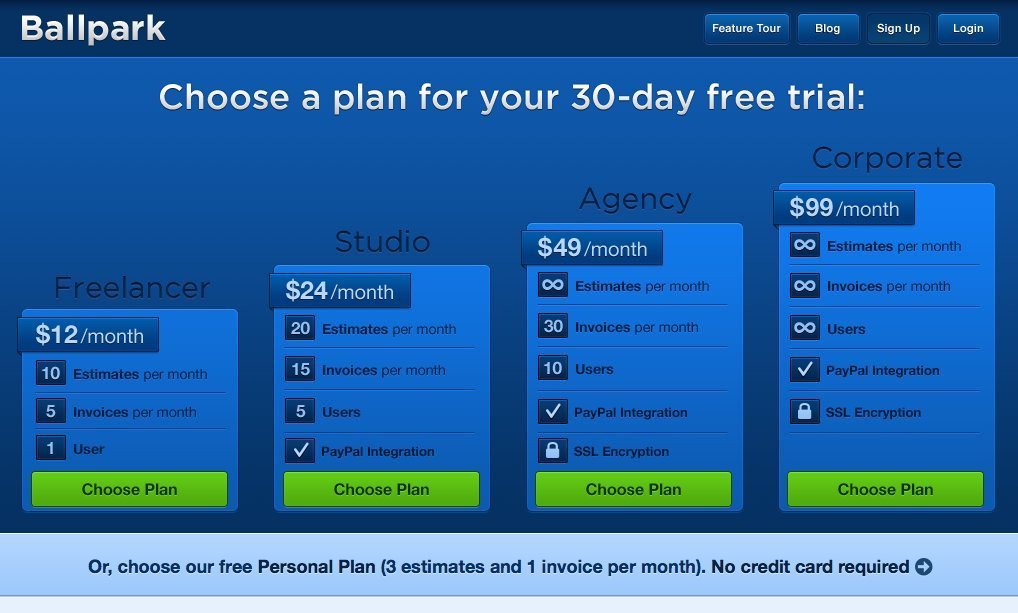

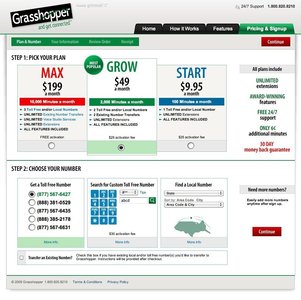

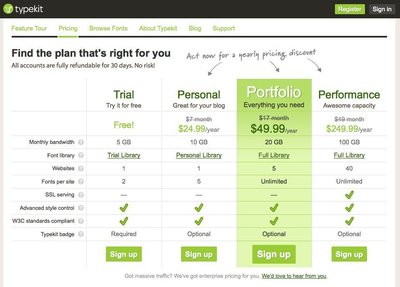

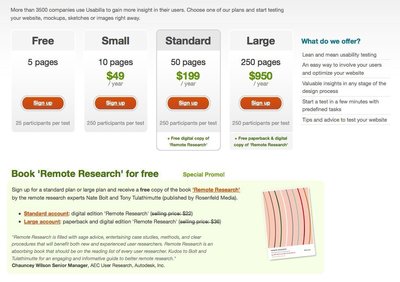

Example

Usage

- Use when you want to make a price seem more fair or cheap – compared to the anchor

- Use when you want to control expectations of users as to how much to give, pay, or receive

This card is part of the Persuasive Patterns printed card deck

The Persuasive Patterns Card Deck is a collection of 60 design patterns driven by psychology, presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!Solution

One of the most used examples of price anchoring is probably the “suggested retail price”. When showing the regular price and the sale price together, the sale price is anchored to the regular price and thus seem like a cheap bargain – even when the sale price wouldn’t have seem like a big deal without the comparison. A cheap price doesn’t become a big deal unless we compare it with a more expensive price – or item. What’s even more: we are inherently bad at remembering what price we typically pay, even for our favorite items.

- Set the initial anchor. Present an initial anchor price or offer to influence subsequent negotiations in your favor.

- Anchor within an acceptable range. A high price makes all others seem cheaper as long as the high price is within an acceptable and plausible range. When anchored within an acceptable range, people tend to accept the anchor rather than start adjusting down.

- Experience weakens the effect. Anchoring is more effectful dealing with new concepts or objects and is weaker in effect dealing with individuals with higher cognitive ability or when dealing with those who have experience buying the product you’re selling.

Rationale

The first piece of information offered tend to automatically become the anchor from which subsequent judgments are made. Nothing is cheap or expensive by itself, but it could be, compared to something else. Anchoring can influence whether we find a product good or not – and in some cases whether we think it is fair to pay or to be paid for a product or service. People will anchor whether you intend for them to do so or not.

An initial value, the “anchor”, serves as a mental benchmark or starting point for estimating an unknown quantity. When first being presented with an anchor value, it is as if the anchor exerts a magnetic attraction, pulling estimates closer to itself. Anchoring works – even when the initial anchor doesn’t represent a reasonable number.

By adding a high priced item to your list of products makes everything else near it look like a relative bargain. When we estimate a numerical value we tend to be susceptible to the power of suggestion. Any related value that we hear just before we make our estimate has a big statistical proven impact on what number we’re going to estimate. Even when warned beforehand about the persuasive powers of anchoring we cannot help but relate information presented alongside when we estimate what’s a fair price or value1.

This is also the reason why it’s a good idea to get your number in first in a negotiation rather than letting your opponent name a number first

Discussion

William Hunt1 described two types of anchoring: contrast anchoring and assimilation anchoring. The two types of anchoring have opposite effects.

Contrast anchoring

Contrast anchoring occurs when you compare two stimuli. When you stare into the head-lights of a car, its surroundings look dark.

Here, subjective perceptions are displayed away from the anchor.

Assimilation anchoring

Assimilation anchoring occurs when you have to invent an answer – given one or more possible responses. This is the kind of anchoring played mostly on by marketeers as they list the before price of a discounted product.

Here, responses are drawn toward the anchor.

What qualifies as an anchor

Harry Helson1 listed the following as qualifying for an anchor: “recency, frequency, intensity, area, duration, and higher-order attributes such as meaningfulness, familiarity, and ego-involvement.”

The anchoring effect is one of the most robust cognitive heuristics. It was first coined by Muzafer Sherif in 1958, but revitalised by Tversky and Kahneman’s seminal article on Judgement under uncertainty in 1974.

1 William Poundstone, Hill and Wang (2010). Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value (and How to Take Advantage of it)

2 Price Anchoring, Or Why a $499 iPad Seems Inexpensive by Matthew Amster-Burton

3 Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

4 Anchoring Bias, explained at Decision Lab

5 How Does Anchoring Impact Our Decisions? by Marco Carrasco Villanueva

6 The Anchoring Effect by Andrea J. Caceres-Santamaria

7 Sherif, M., Taub, D., & Hovland, C. I. (1958). Assimilation and contrast effects of anchoring stimuli on judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 55(2), 150–155.

8 The Anchoring Bias at Learning Loop

More examples of the Anchoring pattern See all 11 example screenshots

User Interface Design Patterns

- Forms

- Explaining the process

- Community driven

- Tabs

- Jumping in hierarchy

- Menus

- Content

- Gestures

- Tables

- Formatting data

- Images

- Search

- Reputation

- Social interactions

- Shopping

- Increasing frequency

- Guidance

- Registration

Persuasive Design Patterns

- Loss Aversion

- Other cognitive biases

- Scarcity

- Gameplay design

- Fundamentals of rewards

- Gameplay rewards