Peak-end rule

Design Pattern

This card is part of the Persuasive Patterns printed card deck

The Persuasive Patterns Card Deck is a collection of 60 design patterns driven by psychology, presented in a manner easily referenced and used as a brainstorming tool.

Get your deck!Solution

Conduct user research to discover the peaks (good or bad) in the user experience you provide. Do they match what you expected? End points can be obvious (order fulfillment) or subtle (registration confirmation).

Identify and improve.

Designing for the peak-end rule is another way of not focusing on what is less important; about focusing on what brings the most value to the users’ experience.

- Establish positive peaks and ends. Counteract negative experiences by delivering a clear positive peak- and end-experiences. It can be anything from memorable and enjoyable music, a free sample, a follow-up call, or providing a feeling of success, flow, and accomplishment.

- Map out user emotions. Conduct user research to map out user emotions and how they change over time. Work towards your peaks and ends being positive and accommodate potential negative experiences with positive ones. Use tools like customer journey mapping or empathy mapping to map out user emotions over time to see the full picture. End points can be obvious (order fulfilment) or subtle (registration confirmation). Identify and improve.

- Postpone the end of your experience. Unless your users escapes your experience before time (then the peak and end could be the same), you usually have plenty of opportunities of controlling the end of an experience to ensure it is a positive one. Conduct pro-active after sales care, provide a 30 minute coaching call, or put yourself in a position to learn how you can do better next time.

Rationale

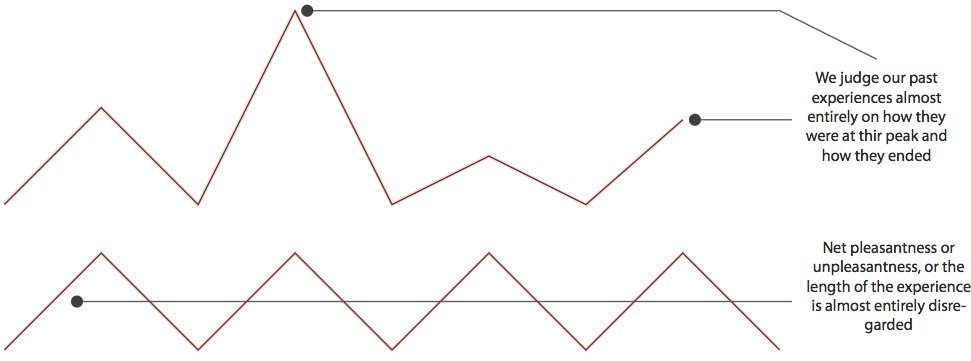

Pleasant or unpleasant, our brains heavily weigh the the most intense felt point and the end when judging an experience, rather than on its total sum or average of every moment. Other information like duration and other logically relevant information aside from the peak and end is not lost, but merely neglected.

The peak end rule is a heuristic in which we judge our past experiences almost entirely on how they were at their peak (whether pleasant or unpleasant) and how they ended1. When we do this we discard virtually all other information, including net pleasantness or unpleasantness and how long the experience lasted.

We only remember certain details of a whole experience; the peak and the end. Whether most parts of the experience were acceptable is without influence on the user’s perception of the experience as a whole. An acceptable experience is often neither memorable, nor differentiating and will not be what makes or brakes your product.

Designing for the peak-end rule is about designing for the moments of truth. Moments of truth are where users experience how poor or good your product really is, and hopefully how it will help them kick ass. A sure moment of truth is at the end of an experience, but there are more. Find your product’s moments of truth through user research and address them. Emphasize them. Turn up the volume of the peak as much as possible and make sure it is pleasant so that it will leave a great lasting impression. Make sure that your peak and end is memorable, branded, satisfactory and different from your competitors.

An interesting twist to the peak-end rule was found when it came to measuring the experienced discomfort of pain. Consider the series 2-5-8 and 2-5-8-4 in which the numbers refer to reports of pain provided on a 10-point scale every 5 minutes. Rationally, adding 5 extra minutes of pain will only increase total discomfort, although experiments showed the longer period of pain (20 minutes), but with a period of diminished discomfort in the end, were rated less discomforting than the shorter period of pain (15 minutes), but with an increased discomfort in the end.

An episode, in which discomfort increases gradually to a high level, is evaluated similarly to an episode in which discomfort is high throughout. Furthermore, when test subjects were asked to evaluate moments, duration was completely neglected until they reminded themselves that it is better for episodes of discomfort to be short rather than long.

Discussion

Why the peak is memorable

The peak-end rule can be explained by several factors. First, we have a tendency to remember intensely emotional events better than less intensely emotional events567. Furthermore, this bias for more intense emotional experiences is evident in nostalgic preferences8.

Why the end is memorable

People exhibit serial position effects such that they have better memory for both the beginning and end of sequences, phenomena known as primacy bias and recency bias, respectively.

The memory bias for the end can be explained by the recency effect: we have better emotional memory for the end of an experience rather than the beginning9.

Although coined by behavioral economist, Daniel Kahnemann, the peak-end rule can be explained by several factors. First, we have a tendency to remember intensely emotional events better than less intensely emotional events. Furthermore, this bias for more intense emotional experiences is evident in nostalgic preferences. This explains the peak. The memory bias for the end can be explained by the recency effect: we have better emotional memory for the end of an experience rather than the beginning.

1 Kahneman, Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology, 1999

2 Peak-end rule shown graphically by Greg Ness

3 Peak-end rule at Coglode.com

4 Peak-end rule at Wikipedia.org

5 Dutta, Satrajit; Kanungo, Rabindra N.; Freibergs, Vaira (1972). “Retention of affective material: Effects of intensity of affect on retrieval”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 23 (1): 64–80.

6 Ochsner, Kevin N. (2000). “Are affective events richly recollected or simply familiar? The experience and process of recognizing feelings past”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 129 (2): 242–261

7 Morewedge, Carey K.; Gilbert, Daniel T.; Wilson, Timothy D. (2005). “The Least Likely of Times How Remembering the Past Biases Forecasts of the Future”. Psychological Science. 16 (8): 626–630

8 Morewedge, Carey K. (2013). “It Was a Most Unusual Time: How Memory Bias Engenders Nostalgic Preferences”. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 26 (4): 319–326

9 Garbinsky, Emily N.; Morewedge, Carey K.; Shiv, Baba (2014). “Interference of the End Why Recency Bias in Memory Determines When a Food Is Consumed Again”. Psychological Science. 25 (7): 1466–1474.

10 The Peak-end Rule at Learning Loop

User Interface Design Patterns

- Forms

- Explaining the process

- Community driven

- Tabs

- Jumping in hierarchy

- Menus

- Content

- Gestures

- Tables

- Formatting data

- Images

- Search

- Reputation

- Social interactions

- Shopping

- Increasing frequency

- Guidance

- Registration

Persuasive Design Patterns

- Loss Aversion

- Other cognitive biases

- Scarcity

- Gameplay design

- Fundamentals of rewards

- Gameplay rewards